Last year, there was rarely a week when international attention wasn’t on China.

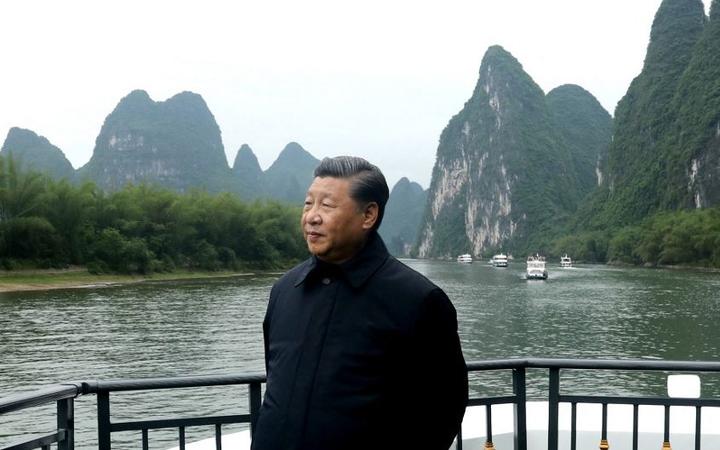

President Xi Jinping currently heads all branches of the Chinese Community Party, the government and the military. Photo: AFP

President Xi Jinping currently heads all branches of the Chinese Community Party, the government and the military. Photo: AFP

Disappearing celebrities, billionaire crackdowns, the Evergrande fiasco, hypersonic missile tests, Hong Kong activist arrests, trade wars, climate goals, Covid-19.

This was hardly a coincidence.

When President Xi Jinping came into power in 2012, he set out to make his agenda widely known – both domestically and internationally.

Unlike his predecessor Hu Jintao – a man of mystery who carried the stereotype of being dull and wooden – Xi has fiercely asserted himself on the world stage.

While at home, he has strategically consolidated power, and enforced sweeping structural reforms in Chinese economy and society that have transformed the country at warp speed.

In the last few years, the high-profile leader has been ramping up his bold diplomatic rhetoric, stamping out opponents, and spreading the country’s tentacles of influence across the Pacific, the South China Sea, Africa and beyond.

And after abolishing presidential term limits in 2018, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in November last year passed a “historic resolution” elevating Xi’s authority to the same pedestal as era-defining leaders Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping.

It seems unlikely the president will be shrinking away anytime soon.

He currently heads all branches of the CCP, government and military, and the 68-year-old’s sights are set to inevitably extend his rule into a third five-year term this year.

Let’s look back at some of his signature moves over the past nine years, and what the future holds for China and the world under his leadership.

China’s biggest anti-corruption crackdown

Introduced soon after becoming chairman of the CCP, Xi’s pledge to crackdown on “tigers and flies” – high- and low-level officials – has become China’s most sweeping anti-corruption campaign.

It has been both his greatest challenge and strongest political weapon.

“He inherited a communist regime, and the Chinese Communist Party was facing a lot of challenges,” Dr Ming Xia, a professor of political science at the City University of New York, said.

Xi arrived when China was basking in the glow of its economic golden years.

For two decades, China had the fastest-growing economy in the world and entrepreneurs were becoming billionaires seemingly overnight.

Leading with the catchcry, “to get rich is glorious”, the reforms of supreme leader Deng in the 70s and 80s helped pave the way for the country’s rapid accumulation of wealth.

The reforms of Deng Xiaoping, seen here at an event in Beijing in 1975, helped many Chinese accumulate great wealth. Photo: AFP

The reforms of Deng Xiaoping, seen here at an event in Beijing in 1975, helped many Chinese accumulate great wealth. Photo: AFP

This surged to new heights in the succeeding decades, but with little regulation a culture of corruption was allowed to spread throughout the business world and into the CCP ranks.

Well-connected Chinese business tycoon Desmond Shum detailed the extent of the political palm-greasing in his memoir Red Roulette.

On any given night, he said entrepreneurs would host members of the communist party elite in private hotel dining rooms, buying favours to seal lucrative business deals.

Wooing government officials with $A1000 ($NZ1060) bowls of maw fish soup, $25,000 watches and so many deal-brokering trips to the bathhouse that one employee’s skin started peeling off was “just the cost of doing business in China in the 2000s”, Shum told the ABC.

4 million snared in the great party purge

Focusing much of his attention within the CCP itself, in 2014 Xi set an example when ex-security chief Zhou Yongkang became the most senior Chinese official to be arrested and expelled from the Communist Party for corruption.

There were many more to come. By 2018, the campaign had reportedly snared more than 2 million party, government, military, and state-owned company officials.

According to Professor Xia, that number now stands at around 4 million.

“This purge has been a chance for him to be regarded as a meat grinder. As this meat grinder he is working very fast and hurting the Chinese elite,” he said.

Singaporean former diplomat and political commentator Kishore Mahbubani sees the crackdown as one of Xi’s great achievements, saying he has so far successfully overcome “many big challenges like growing corruption and factionalism in the party”.

“He’s been riding a very wild horse over the last nine years, and kept going at a steady pace,” he said.

While the anti-corruption drive has instilled more trust among some parts of society, the president has been accused of using the campaign to neutralise political opponents.

“We know that this anti-corruption has been used – and to some extent abused – by Xi Jinping to purge his political opponents or competitors,” Professor Xia said.

Shum claims that many corrupt officials are still within the top echelons of the political party today, and they were being protected through Xi’s “selective” campaign.

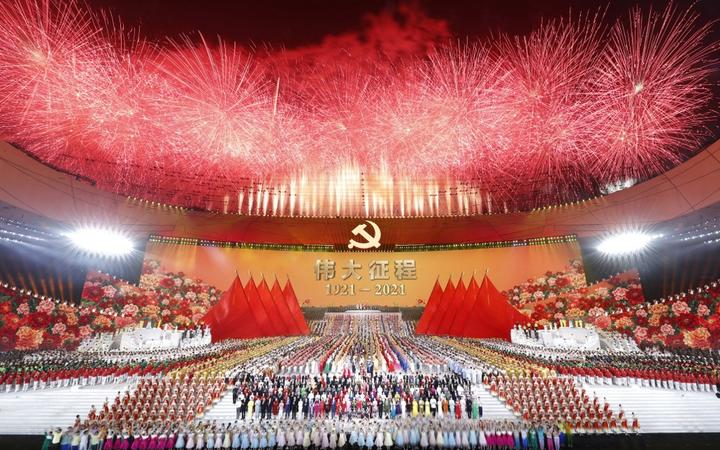

A celebration of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party last July. A critic claims it still has many corrupt officials. Photo: AFP

A celebration of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party last July. A critic claims it still has many corrupt officials. Photo: AFPCelebrities and moguls caught in the disappearing act

Xi has positioned himself as a dictator who has no room for dissent or disobedience at any level.

Recently, a wave of high-profile figures have gone missing from the public eye after making public statements against the government.

Movie star Fan Bingbing, gene-editing scientist He Jiankui, and most recently tennis star Peng Shuai are among the many who seemingly vanished for several weeks.

Tennis star Peng Shuai is among Chinese celebrities who have disappeared for periods after criticising the government. Photo: PHOTOSPORT

Tennis star Peng Shuai is among Chinese celebrities who have disappeared for periods after criticising the government. Photo: PHOTOSPORT

China’s richest man, Alibaba founder Jack Ma, disappeared for three months after giving a controversial speech in October 2020 blasting China’s regulatory system.

Since reappearing, Alibaba has been fined $A3.8 billion for anti-competitive behaviour, and the flamboyant billionaire’s net wealth has been plummeting.

Another well-known businessman, real estate tycoon Ren Zhiqiang, reportedly disappeared in 2020 after he called Xi a “clown” for his handling of the coronavirus crisis in China.

He was later sentenced to 18 years in prison for corruption.

Real estate tycoon Ren Zhiqiang is now in prison. Photo: AFP

Real estate tycoon Ren Zhiqiang is now in prison. Photo: AFP

Shum, whose business deals came very close to the core of power, has also felt the force of party pressure.

His ex-wife and business partner Duan (Whitney) Weihong – who at the time was one of the richest women in China – disappeared in Beijing in 2017.

She re-emerged after four years shortly before Shum’s memoir was due to be released in September 2021, calling him with a warning not to release the book.

The government has never acknowledged taking Duan, but Shum, who has lived in Britain since 2015, says there’s “no question” they are responsible for her disappearance.

China’s ‘darkest period’ for human rights abuses

In 2013, Xi introduced new laws that essentially made arbitrary and secret detentions legal under Chinese law.

Regardless of citizenship, these complex laws can be used to strip detainees of their rights on the grounds of “national security”.

It also allows for suspects to be held in custody for up to six months under the “residential surveillance at a designated location” (RDSL) scheme, which cuts suspects off from the outside world.

Yang Hengjun Photo: AFP

Yang Hengjun Photo: AFP

Australian television anchor Cheng Lei, who has worked for the Chinese government’s English news channel, was held in custody under the RDSL scheme in 2020.

Australian writer Yang Hengjun is also among those who has been placed under residential surveillance.

China has also been accused of human rights abuses over its treatment of Uyghurs in the north-west region of Xinjiang.

The United Nations and rights groups allege that 1 million Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities have been disappeared or are being held in internment camps in Xinjiang.

Chinese authorities insist the camps are vocational centres, dismissing ongoing claims of atrocities against minorities in the region as “the biggest lie of the century”.

The US government has declared that Beijing’s policies against the Uyghurs amount to genocide and crimes against humanity.

Legislatures in Britain, Belgium, the Netherlands and Canada have done the same.

The US House of Representatives recently passed a bill banning imports from Xinjiang, over forced labour concerns.

China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin hit back saying that “the so-called forced labour and genocide in Xinjiang are entirely vicious rumours”.

China’s crackdown on freedoms in Hong Kong has also triggered widespread global condemnation.

It introduced a sweeping national security law in the city in wake of mass anti-government protests in 2019.

Since coming into force in June 2020, dozens of activists and democratic politicians have been jailed, or are in self-exile, and some international rights groups have left the city.

Human Rights Watch says under President Xi, China is facing its “darkest period for human rights since the 1989 massacre that ended the Tiananmen Square democracy movement”.

Push for common prosperity

In preparing for a third term, Xi has been turning towards inequality, seeking to narrow the gap between rich and poor with a push for “common prosperity”.

Last year, he has used the term “common prosperity” more than 65 times in his speeches, calling it the “original quintessence” of socialism.

The president has called for “excessive incomes” to be “reasonably adjusted”, saying that it was necessary to “encourage high-income earners and enterprises to give back more to society”.

This has involved asking big companies to put money into philanthropy, with tech giants, including Alibaba and Tencent, pledging billions of dollars to support the campaign.

While experts say low-income households may welcome the move, political pressure on companies could ultimately harm both the rich and poor, and stifle economic growth.

“The economy is not doing well, and the stock market and housing market are signs of that … many big companies are going bankrupt, and many people are losing money,” Professor Xia said.

The plight of debt-stricken real estate company Evergrande has already exposed the risks of the government’s regulatory crackdown.

In an attempt to rein in house prices and reduce debt levels, regulators tightened limits on borrowing by China’s real estate industry.

This led to the near collapse of the country’s largest property developer which has been struggling to make bond payments.

It prompted fear and speculation that the world was facing its next “Lehman Brothers moment”.

Society suppressed under Xi ‘Thoughts’

With Xi’s reign came a new ideology and brand of Chinese nationalism, which in 2017 was enshrined into the party constitution.

He is the only leader, other than Mao, to have an eponymous ideology included in the document while in office.

Central to what’s been called “Xi Jinping Thought” is China’s continued rise as a global power, promoting the party and Xi on top as the guiding force.

The president’s philosophies have been introduced into the national curriculum, splashed across the internet and billboards, and exist as an app for party members to read and be quizzed on daily.

In 2021, the government placed a three-hour gaming limit per week on minors, and cracked down on “effeminate” men and celebrity fandom in a bid to steer China’s culture industry in a “healthier” direction.

“The Chinese Communist Party has tightened its control over the society and I think this is counterproductive,” Professor Xia said, adding that “many ordinary people are angry”.

Xi and the world

While leaders before him have opted to keep a low profile, under President Xi China has become more assertive with international diplomacy, ramping up military threats, inflammatory language and economic punishment.

To sustain the country’s global rise, Xi has been investing heavily in the $1 trillion international Belt and Road trade and infrastructure initiative, and modernising China’s military.

This military presence has been on display with repeated aggressive actions in the contested South China Sea and several instances of planes being flown into Taiwan’s Air Defence Identification Zone as Xi vows to “reunify” the island.

This “Wolf-Warrior” approach to diplomacy has been ruffling international feathers, and increasingly straining China’s relationships with the US and Australia.

Professor Mahbubani said that alienating the American business community was Xi’s “major mistake” during his leadership.

“[It] used to be the number one supporter of close relations between US and China,” he said.

US President Joe Biden meets with China’s President Xi Jinping during a virtual summit last November. Photo: AFP

US President Joe Biden meets with China’s President Xi Jinping during a virtual summit last November. Photo: AFP

However, when it comes to the trade war and spats between Beijing and Canberra, he said it’s Australia who should learn to adapt.

“Many of the people in South-East Asia share the same apprehensions of China that Australia has, but you learn how to live and adapt to a stronger and more powerful China,” he said.

“So for a start, you don’t publicly insult China. But even if Australia chooses to publicly insult China, you have to accept that there will be consequences that flow as a result.”

Looking to the future

“If you put all these things together and ask the question, ‘Has Xi Jinping succeeded?’ My answer is no,” Professor Xia said.

“He is becoming unsafe, intoxicated, and abusing his personal power. I think this is something very dangerous.”

Xi has set many of his goals to the 2035 benchmark. If he makes it through those two further five-year cycles, he will have ruled China for 20 years.

In 2035, he will be 82 years old.

While some people in the West are calling Xi a dictator of an authoritarian regime, Professor Mahbubani says the focus should not be on substance over length.

He believes that the Chinese government is “more popular than it has ever been” and there shouldn’t be an expectation for societies to be “carbon copies or replicas of the West”.

“In the Chinese political tradition, when they have a strong ruler, who delivers concrete benefits to the Chinese people, he’s considered the best ruler for China,” he said.

“When China succeeds, and does well, it will not function according to the western model.”

Leave A Comment