By air, land, and sea, Russia has launched a devastating attack on Ukraine, a European democracy of 44 million people, and its forces are on the outskirts of the capital, Kyiv.

For months, President Vladimir Putin denied he would invade his neighbour, but then he tore up a peace deal, sending forces across borders in Ukraine’s north, east and south.

As the number of dead climbs, he stands accused of shattering peace in Europe. What happens next could jeopardise the continent’s entire security structure.

Why have Russian troops attacked?

Russian troops are advancing on Ukraine’s capital from several directions after Russia’s leader ordered the invasion. In a pre-dawn TV address on 24 February, he declared Russia could could not feel “safe, develop and exist” because of what he claimed was a constant threat from modern Ukraine.

Airports and military headquarters were hit first, near cities across Ukraine, then tanks and troops rolled into Ukraine from the north, east and south – from Russia and its ally Belarus.

Many of President Putin’s arguments were false or irrational. He claimed his goal was to protect people subjected to bullying and genocide and aim for the “demilitarisation and de-Nazification” of Ukraine. There has been no genocide in Ukraine: it is a vibrant democracy, led by a president who is Jewish.

“How could I be a Nazi?” said Volodymr Zelensky, who likened Russia’s onslaught to Nazi Germany’s invasion in World War Two.

President Putin has frequently accused Ukraine of being taken over by extremists, ever since its pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovych, was ousted in 2014 after months of protests against his rule.

Russia then retaliated by seizing the southern region of Crimea and triggering a rebellion in the east, backing separatists who have fought Ukrainian forces in a war that has claimed 14,000 lives.

Late in 2021, Russia began deploying big numbers of troops close to Ukraine’s borders, while repeatedly denying it was going to attack. Then Mr Putin scrapped a 2015 peace deal for the east and recognised areas under rebel control as independent.

Russia has long resisted Ukraine’s move towards the European Union and the West’s defensive military alliance, Nato. Announcing Russia’s invasion, he accused Nato of threatening “our historic future as a nation”.

How far will Russia go?

It is now clear that Russia is seeking to overthrow Ukraine’s democratically elected government. Its aim is that Ukraine be freed from oppression and “cleansed of the Nazis”.

President Zelensky said he had been warned “the enemy has designated me as target number one; my family is target number two”.

This false narrative of a Ukraine seized by fascists in 2014 has been spun regularly on Kremlin-controlled TV. Mr Putin has spoken of bringing to court “those who committed numerous bloody crimes against civilians”.

What Russia’s plans are for Ukraine are unknown, but it faces stiff resistance from a deeply hostile population.

In January, the UK accused Moscow of plotting to install a pro-Moscow puppet to lead Ukraine’s government – a claim rejected at the time by Russia as nonsense. One unconfirmed intelligence report suggested Russia aimed to split the country in two.

In the days before the invasion, when up to 200,000 troops were near Ukraine’s borders, Russia’s public focus was purely on the eastern areas of Luhansk and Donetsk.

By recognising the separatist areas controlled by Russian proxies as independent, Mr Putin was telling the world they were no longer part of Ukraine. Then he revealed that he supported their claims to far more Ukrainian territory.

The self-styled people’s republics cover little more than a third of the whole of Ukraine’s Luhansk and Donetsk regions, but the rebels covet the rest, too.

How dangerous is this invasion for Europe?

These are terrifying times for the people of Ukraine and horrifying for the rest of the continent, witnessing a major power invading a European neighbour for the first time since World War Two.

Dozens have died already in what Germany has dubbed “Putin’s war”, both civilians and soldiers. And for Europe’s leaders, this invasion has brought some of the darkest hours since the 1940s.

It was, said France’s Emmanuel Macron, a turning point in Europe’s history. Recalling the Cold War days of the Soviet Union, Volodymyr Zelensky spoke of Ukraine’s bid to avoid a new iron curtain closing Russia off from the civilised world.

Press handout showing Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on the front line

Press handout showing Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on the front lineFor the families of both armed forces, there will be anxious days ahead. Ukrainians have already suffered a gruelling eight-year war with Russian proxies. The military has called up all reservists aged 18 to 60 years old.

Top US military official Mark Milley said the scale of Russian forces would mean a “horrific” scenario, with conflict in dense urban areas.

This is not a war that Russia’s population was prepared for, either, as the invasion was rubber-stamped by a largely unrepresentative upper house of parliament.

The invasion has knock-on effects for many other countries bordering both Russia and Ukraine. Five countries are seeing an influx of refugees, while the UN children’s agency says its projected scenario is for up to five million refugees. Poland, Moldova, Romania, Slovakia and Hungary are all braced for arrivals.

What can the West do?

Nato has put warplanes on alert, but the Western alliance has made clear there are no plans to send combat troops to Ukraine itself. Instead, they have offered advisers, weapons and field hospitals.

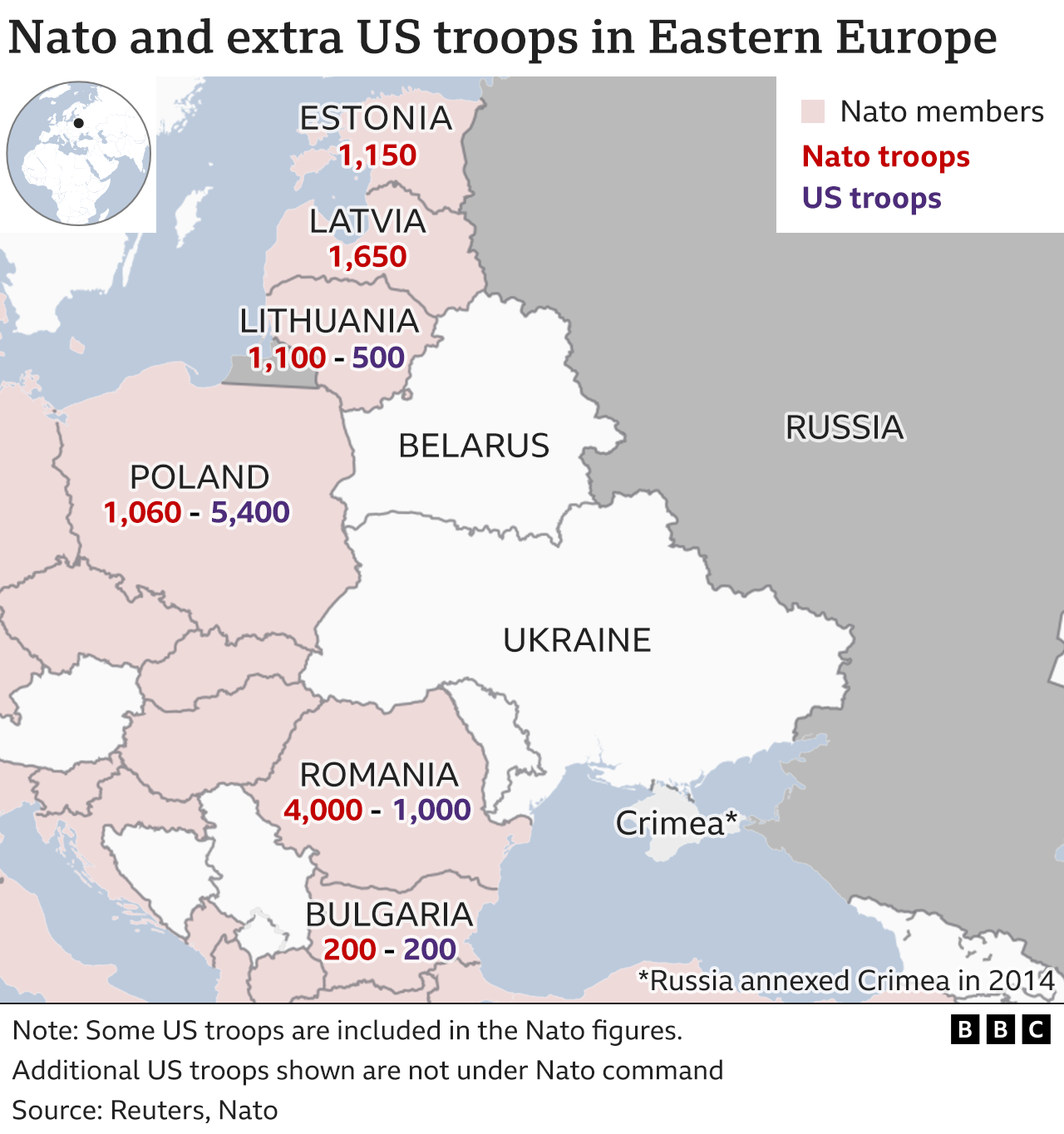

Meanwhile, 5,000 Nato troops have been deployed in the Baltic states and Poland. Another 4,000 could be sent to Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary and Slovakia.

At the same time, the West is targeting Russia’s economy, financial institutions and individuals:

- The EU and UK have imposed personal sanctions on President Putin and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov

- The EU also wants to restrict Russian access to capital markets and cut off its industry from latest technology and defence. It has also targeted 351 MPs who backed Russia’s recognition of the rebel-held regions

- Germany has halted approval on Russia’s Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, a major investment by both Russia and European companies

- The US is targeting 10 of Russia’s biggest financial institutions, with about 80% of its banking assets, so they will struggle to do transactions in dollars or euros

- The UK says all major Russian banks would have their assets frozen, with 100 individuals and entities targeted; and Russia’s national airline Aeroflot will also be banned from landing in the UK.

Ukraine has urged its allies to stop buying Russian oil and gas. The three Baltic states have called on the whole international community to disconnect Russia’s banking system from the international Swift payment system. That could badly affect the US and European economies and Germany says is reluctant to agree to it.

The Russian city of St Petersburg will no longer be able to host this year’s Champions League final for security reasons.

What does Putin want?

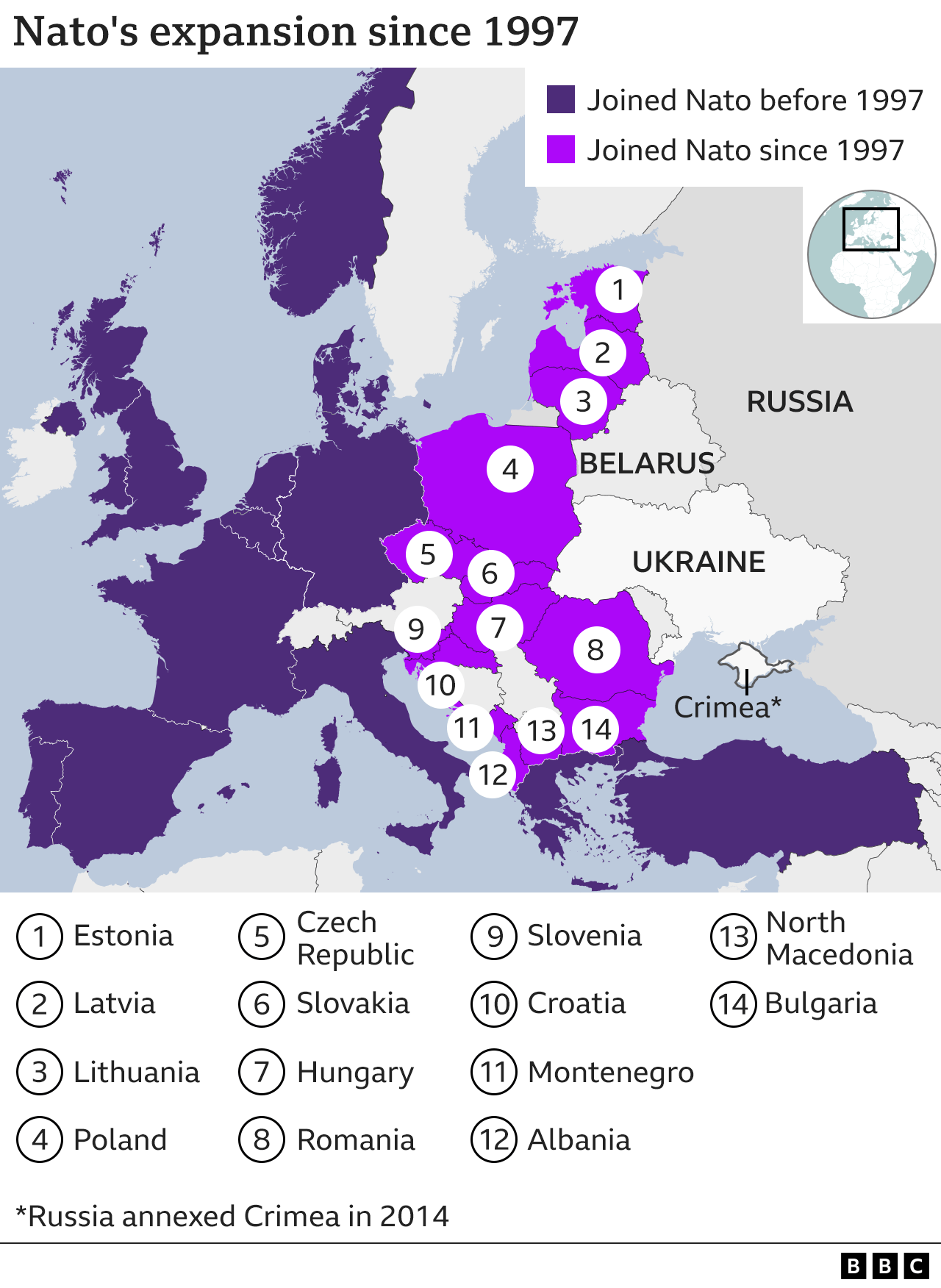

President Putin partly blamed his decision to attack on Nato’s eastward expansion. He earlier complained Russia had “nowhere further to retreat to – do they think we’ll just sit idly by?”

Ukraine is seeking a clear timeline to join Nato and Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov explained: “For us it’s absolutely mandatory to ensure Ukraine never, ever becomes a member of Nato.”

Last year, President Putin wrote a long piece describing Russians and Ukrainians as “one nation”, and he has described the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991 as the “disintegration of historical Russia”.

He has claimed modern Ukraine was entirely created by communist Russia and is now a puppet state, controlled by the West.

President Putin has also argued that if Ukraine joined Nato, the alliance might try to recapture Crimea.

But Russia is not just focused on Ukraine. It demands that Nato return to its pre-1997 borders.

Mr Putin wants Nato to remove its forces and military infrastructure from member states that joined the alliance from 1997 and not to deploy “strike weapons near Russia’s borders”. That means Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the Baltics.

In President Putin’s eyes, the West promised back in 1990 that Nato would expand “not an inch to the east”, but did so anyway.

That was before the collapse of the Soviet Union, however, so the promise made to then Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev only referred to East Germany in the context of a reunified Germany. Mr Gorbachev said later “the topic of Nato expansion was never discussed” at the time.

What has Nato said?

Nato is a defensive alliance with an open-door policy to new members, and its 30 member states are adamant that will not change.

There is no prospect of Ukraine joining for a long time, as Germany’s chancellor has made clear.

But the idea that any current Nato country would give up its membership is a non-starter.

Is there a diplomatic way out?

Not for now. Ukraine has called for talks, but Russia says they can only be held on condition that Kyiv agrees to surrender and demilitarise, and that will not happen.

As well as the war, any eventual deal will need to involve with the West in the east and arms control.

REUTERS/The Russian and US presidents have spoken several times via video link and over the phone

REUTERS/The Russian and US presidents have spoken several times via video link and over the phone

The US had offered to start talks on limiting short- and medium-range missiles, as well as on a new treaty on intercontinental missiles. Russia wanted all US nuclear arms barred from beyond their national territories.

Russia had been positive towards a proposed “transparency mechanism” of mutual checks on missile bases – two in Russia, and two in Romania and Poland.