The diplomatic fireworks in Anchorage turned out to be a prelude to a new round of sanctions war between China and the Western alliance.

Just as the Americans’ profession of defending universal values and a rules-based international system was met with a fierce response from the Chinese side in Alaska, so an extraordinarily coordinated effort by the United States, Britain, Canada and the European Union to impose sanctions on China was met with a tit-for-tat retaliation from Beijing.

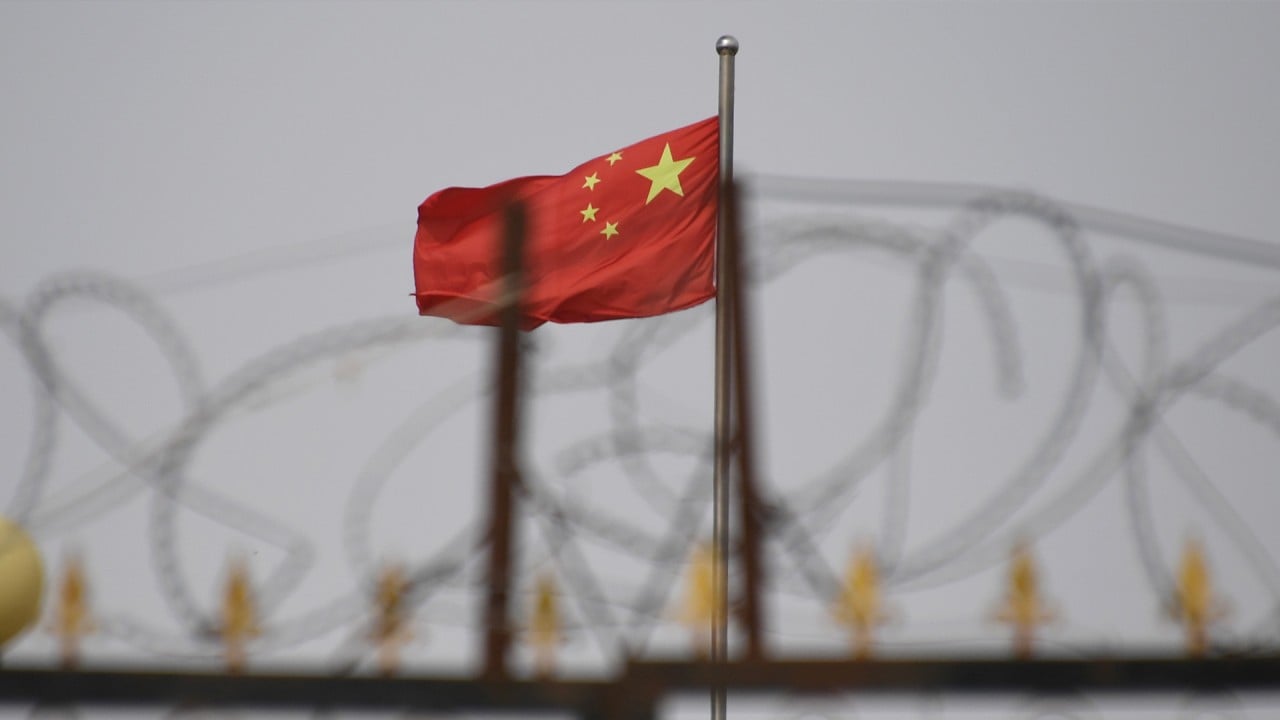

Ostensibly, the Western sanctions are over China’s alleged ill-treatment of Uygur Muslims in Xinjiang. But the unmistakably intended message, to China and the world, is that the Western alliance is back, and the allies don’t mind if it is led by the US – against China.

After four years of Donald Trump and his brand of unilateralism, China has been told not to bother trying to divide and conquer by playing one bloc or country against another. But what is equally significant is that Beijing has been ready to fight back immediately with formal sanctions, something it had avoided until recently.

Traditionally, China has been reluctant to use sanctions as a formal tool against foreign entities or countries, for both ideological and practical reasons. A key principle of Chinese diplomacy has been respect for the sovereignty of nations, and Beijing has long considered sanctions to be a tool of Western countries, especially the US, to interfere with the internal affairs of other, usually weaker, nations.

As Yukon Huang, the well-known economist, once observed, Beijing prefers coercive economic measures over formal sanctions. It has, for example, targeted Australia since last year over barley, beef and lamb, wine, cotton, lobsters, timber and coal, usually citing regulatory rather than political or diplomatic reasons.

Coercive economic measures are a display of hard power; formal sanctions show, or pretend to show, both hard power and moral judgment. It’s saying, “Not only do I have the power, but also the moral authority, to judge and punish you.”

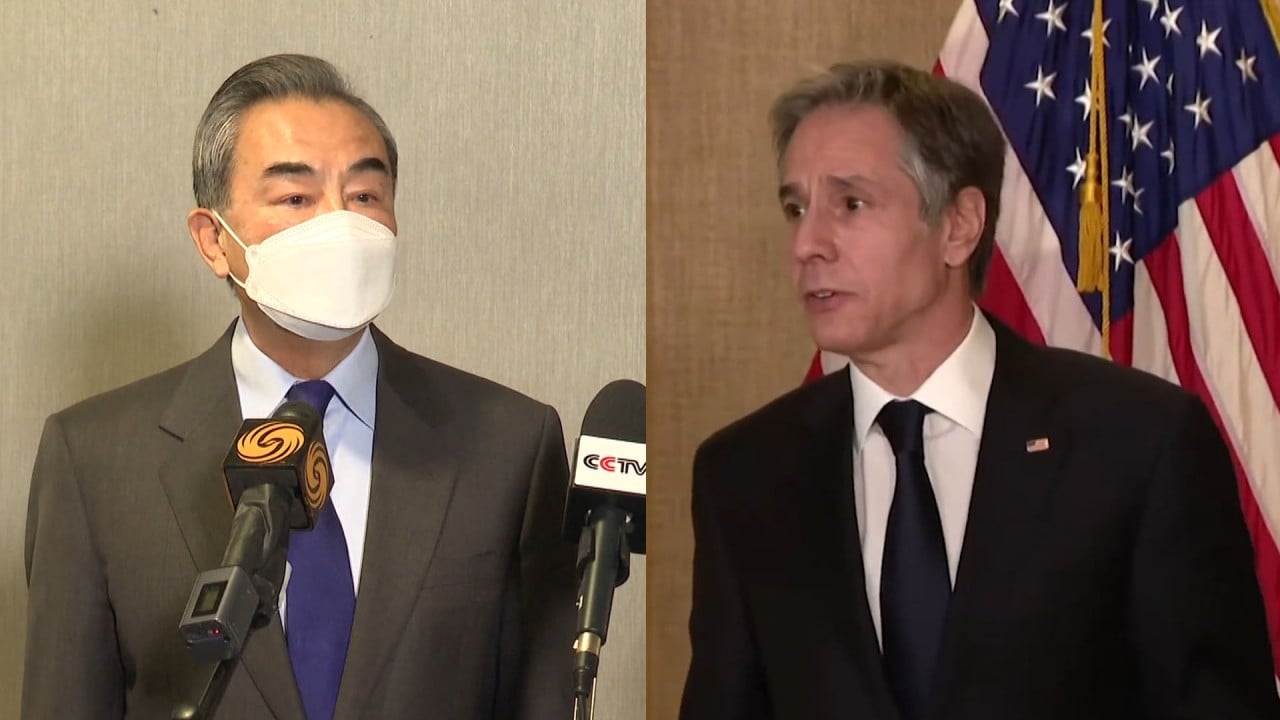

“You people do not have the standing in front of China to claim you are negotiating from a position of superiority,” foreign policy chief Yang Jiechi told his American counterpoint, Antony Blinken, in Anchorage.

But, you ask, aren’t the Western nations standing on moral high ground, at least with respect to the Uygurs? Well, we can argue one way or the other till kingdom come. The worst humanitarian crisis of the 21st century is not in Xinjiang but Yemen, where millions face death, starvation and disease because of a merciless war prosecuted by Saudi Arabia and fully supported by the US. The Saudis were given the green light by Barack Obama, and unconditional support and diplomatic cover by Donald Trump.

If you want to talk about ethnic persecution, what about the Hungarian minority in Ukraine, the Muslims in India-controlled parts of Kashmir, or the Palestinians?

Despite the many conflicts between the Western allies, they clearly want to rebuild their alliance, and China is by far the easiest rallying point. This has been, perhaps, Beijing’s worst diplomatic failure, covered over and its reckoning delayed only because of the ineptitude of the Trump administration.

The Uygurs present the perfect issue for the Western allies to show a united front on political, ideological and moral grounds. It’s intriguing, though, that it’s the Western countries, rather than Islamic ones, that have been shouting the loudest about the Muslim Uygurs.

However, the Joe Biden administration clearly realises it has its own dirty laundry in Yemen and has been quietly putting pressure on Riyadh to end the war. That is why the Saudis have proposed this week a ceasefire with the Houthi rebels, including lifting a blockade on ports that have prevented the delivery of life-saving food and medicine.

This is both a smart and moral thing for the Americans to do in Yemen; the six-year conflict has served no purpose other than causing untold misery and suffering. The Chinese can learn a thing or two here.

While outwardly maintaining a hard line, Beijing can gradually ease and remove restrictive and punitive measures against the Uygurs, and continue with efforts to develop the region economically without undermining their culture, language and heritage.

Let’s call that a moral quid pro quo between the Americans and Chinese for all the bad things they have done respectively in Yemen and Xinjiang.