If central banks don’t lance the QE boil now they probably never will, risking soaring inflation that takes the world back to the 1970s

Countries making up three quarters of global economic output have reached critical vaccination thresholds. Many others have largely covered the most vulnerable cohorts.

The world economy is not going back into a collective lockdown whatever the delta variant may bring. Just as the vaccines have broken the link between cases and death, societies have broken the link between the virus and economic loss. Each wave has a diminishing impact.

Fiscal and monetary largesse in the advanced states overwhelm the residual pockets of damage in the OECD bloc. Pent-up savings and a capex restocking cycle should pick up the baton as state support fades (the US fiscal impulse turns negative this quarter).

The UK is the world’s laboratory for opening up. Unfortunately it has done so with breathtaking incompetence and given the process a bad name.

The error is not the decision to lift curbs. It is a legitimate strategy to open up fully during the peak of summer when 70pc of adults have been fully vaccinated. In a sense it is the original (premature) Vallance strategy of letting the virus run in a controlled fashion to achieve herd immunity, but this time in plausible circumstances. The death rate has fallen to levels that resemble winter flu.

It will soon become clear to market traders across the globe whether British hospitalisations will remain manageable or whether the pandemic again approaches the catastrophism of Professor Neil Ferguson. If the latter, Monday’s rush into the safe-haven bonds – gilts, US Treasuries, Bunds – is indeed the harbinger of something serious.

My own view is that the Ferguson sell-off – most visible in crumbling travel stocks, and a 7pc crash in crude priceslinked to jet fuel demand – is to blame the wrong culprit. Commentators are latching onto Covid to explain financial ructions that have their roots elsewhere.

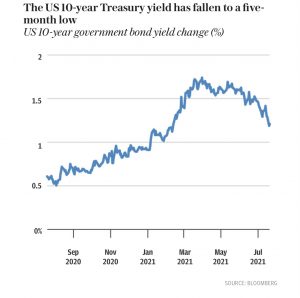

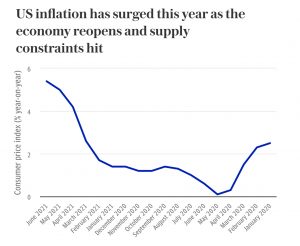

What we really have is a taper tantrum. The Anglo-Saxon central banks have been shocked by the force of the inflation surge and are suddenly turning hawkish in a belated effort to restore their own credibility. The bond markets are pricing in the risk that they will overtighten. This is the “policy error” narrative. Hence the fall in 10-year US yields to 1.2pc, a recession warning.

The financial system has become acutely sensitive to slight tweaks in monetary policy. This is known as the central bank “debt trap”. The Economic Affairs Committee of the House of Lords alluded to this in its report last week – quantitative easing: a dangerous addiction?

“No central bank has managed successfully to reverse its asset purchases over the medium to long-term, and the key issue as they look to halt or reverse quantitative easing is whether it will trigger panic in financial markets that spills over into the real economy,” it concluded.

This blistering report is key to understanding the market events unfolding. It implicitly accuses the Bank of England’s Governor Andrew Bailey and fellow rate-setters of falling captive to political masters, letting rip on inflation, and playing fast and loose with the credibility of British monetary management.

The Bank knew this damning indictment was coming. It is an open secret that former Governor Mervyn King was the éminence grise behind the drafting. There are few precedents for such a rebuke from the heart of the British establishment. It helps explain why the Monetary Policy Committee has changed its tune so precipitously.

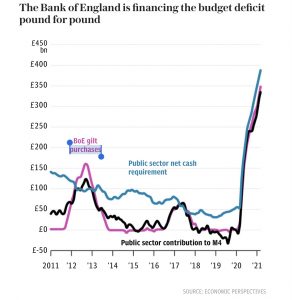

The Lords report strongly suggests that the Bank has been soaking up Treasury debt issuance pound for pound over the last 15 months at the behest of the Government, flirting with Latin American fiscal dominance.

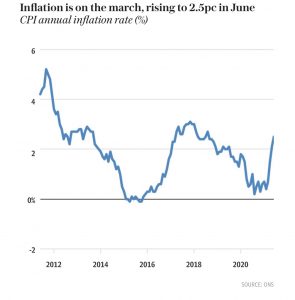

The report said the Bank had failed to offer a scientific justification for what it is trying to achieve with QE, or for why it is continuing to purchase bonds à outrance when the economy is recovering briskly, the housing market is on fire, and inflation keeps overshooting the Bank’s forecasts.

Whether it is due to the wrath of the Lords or the hard data, the Bank is finally tacking hard. Deputy governor Sir David Ramsden last week broached the subject of early bond tapering, confessing that he “wouldn’t be surprised” if inflation hit 4pc later this year. The MPC’s Michael Saunders suggested that a total halt to bond purchases over the next month or two might be a good idea.

A variant of this hawkish turn is underway in the US, where core inflation is at a 30-year high of 4.5pc and the Fed’s regional presidents are in simmering revolt against the ivory tower New Keynesians at the board in Washington.