The Glasgow deal makes incremental progress on the climate crisis but largely kicks the can down the road

So, with the final deal settled, does Cop26 look like a success or failure? The unsatisfactory answer is both, but it’s more the latter than the former.

In relative terms, the agreements and deals made by the 196 nations in Glasgow nudged the world a little closer towards the path to keeping global temperature rises below 1.5C and avoiding the worst of the climate crisis’s impacts.

But in absolute terms, there is still a mountain to climb. Before Cop26, firm pledges to cut emissions by 2030 pointed to 2.7C of global heating – a catastrophe. After, the figure is 2.4C – still a catastrophe.

Longer term promises to go to net zero emissions, notably by India, might possibly restrict heating to 1.8C by the end of the century, but lack the concrete plans to be credible. And 1.8C still means immense suffering to people and the planet.

The key agreements sealed in Glasgow essentially kick the can down the road. Big emitting nations with feeble plans to cut emissions must return in a year to improve them – that is how 1.5C can be said to still be alive. The $100bn a year to pay for clean energy in developing countries promised a decade ago for 2020 will not be delivered until 2023.

Worst of all, a deal to compensate nations for the heatwaves, storms and floods that are already hitting the most vulnerable people was booted into a talking shop. There is currently just $2m in that “loss and damage” fund – a pittance.

The climate emergency is a slow motion disaster and our escape was only ever going to be in slow motion too – remaking a world that has run on fossil fuels cannot happen overnight, particularly in the face of lobbying by rich vested interests.

But the world has been kicking the climate can down the road for three decades now. The Cop26 deal means the next 18 months will truly be make or break.

There are positives to build on. The 196 nations are now firmly fixed on the 1.5C target demanded by the science. For the first time, nations are called on to “phase down” coal and fossil fuel subsidies in a Cop text. As extraordinary as that sounds, it is a landmark that Russia, Saudi Arabia and others tried to erase, although it is regrettable India had the language watered down from “phase out” at the last minute.

Deals on ending the razing of forests by 2030, cutting emissions of methane – a powerful greenhouse gas – and making green technology like electric cars the cheapest option globally are all encouraging, even if the pact to end sales of fossil fuel powered cars stalled, with the major markets and manufacturers failing to sign up.

An end to international finance for coal power will also dent emissions and some of the most outrageous loopholes in proposed rules for a global carbon market rules were closed – but not all, and cheats may yet prosper.

Other negatives included the initiative claiming to put the world’s financial institutions – which bankroll the fossil fuel industry – on a green path but it represented tiny steps.

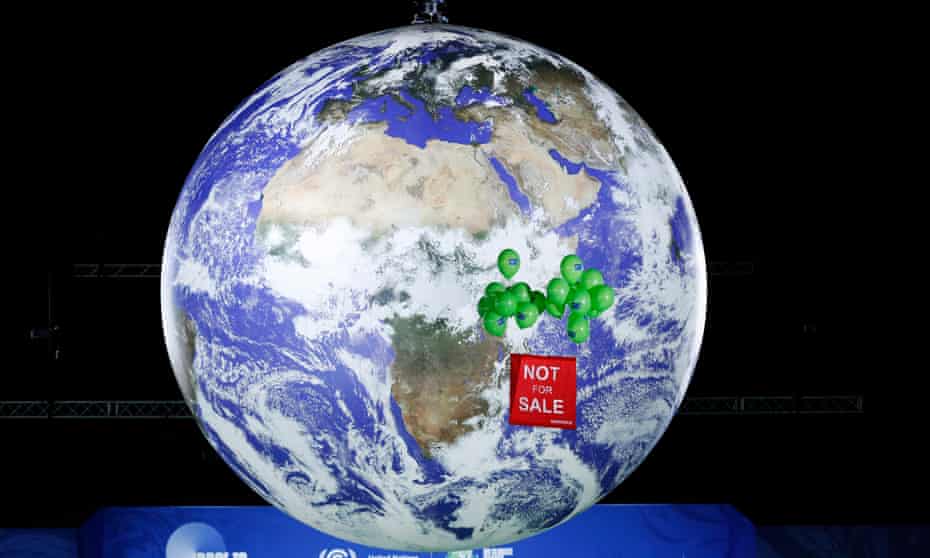

The reaction of countries to the Glasgow deal is calibrated by the imminence of the threats they face and the resources they have to cope. The US said it was “a very important step forward”. Aminath Shaunam, the delegate from the fast-disappearing island state of the Maldives, said: “This deal does not bring hope to our hearts. It will be too late for the Maldives. [We] implore you to deliver the resources we need in time.”

UN climate summits are more complex these days, according to Saleemul Huq, a COP veteran from Bangladesh: “We now have to deal with two climate change problems: the old one of preventing catastrophic impacts for everyone if we go above 1.5C and a new one of dealing with the loss and damage already happening due to the increase already of 1.1C.”

Cop26 could have and should have achieved more. So why did it not? The Covid pandemic made the essential diplomatic leg work ahead of the summit hard to conduct. The pandemic also curtailed the protests by millions of young people, whose voice and moral authority was so powerful.

The host, the UK, may not have helped build the trust required to land a strong deal by cutting overseas aid in the run up, for which it was called out in the halls of Glasgow. Failing to join an alliance to phase out oil and gas at its own summit and planning a new oil field at home cannot have helped either.

In the closing hours of Cop26, countries repeatedly said they were accepting weaker proposals than they wanted in the “spirit of compromise”. But there is no compromising with the science of global heating. UN secretary general António Guterres said in Glasgow that the goal of 1.5C was “on life support”. It still is.

Leave A Comment