In the EU, the rapid growth has fuelled fears about the impact of these investments on jobs, technology and Europe’s long-term industrial capacity, sparking calls for more oversight. In this context, some see the investment screening mechanism the EU put in place in 2019 as targeted at Chinese companies.

During the pandemic, growing concerns that vital European technology and knowhow could be vulnerable to foreign takeover because of the economic downturn led the European Commission to issue guidelines for its member states. To bring greater clarity to the situation, the EU has negotiated a deal with China – the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment – to replace the current 26 individual country agreements that exist between all individual member states except Ireland.

The agreement is currently blocked for political reasons, following tit for tat sanctions related to the EU’s concerns about human rights violations in Xinjiang province. But the debate on how best to adapt to this new context is unlikely to go away.

Much of what we know about Chinese investment in the EU is anecdotal. In a recent paper, my colleagues and I undertook a thorough analysis of these investments using detailed Chinese data. Our work highlights the great variety of Chinese investments in the EU, in terms of the types of industry and companies involved and different firms’ motivations for investing.

Why China invests in Europe

Our paper is based on a database covering nearly 800 Chinese investments in industrial sectors in Europe between 2006 and 2015.

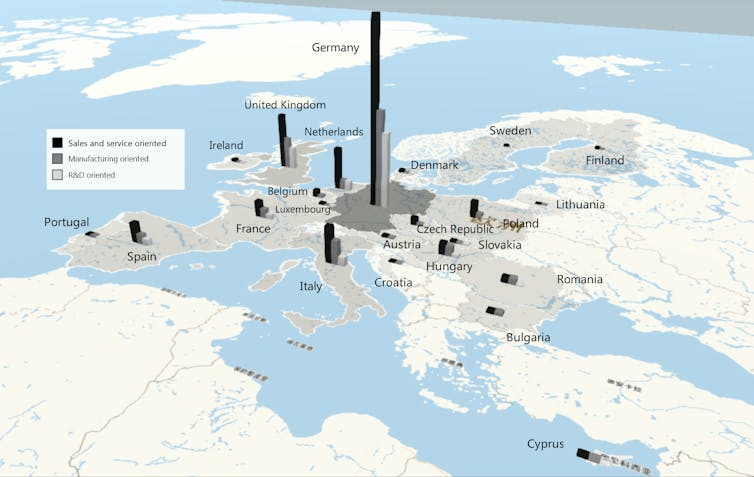

Chinese companies must declare their overseas investments to the government and these declarations provide valuable information about where they are investing and why. The declarations include the country and industry they invested in and whether the investment involve supporting their sales to Europe, manufacturing goods locally or conducting research and development.

Germany was the top choice for Chinese companies investing Europe, followed by UK, Netherlands and Italy.

Over time, we found that investments for sales have fallen from 70% to less than half of total investments, while research and development and manufacturing have become more important. This shows that the notion that Chinese firms see Europe purely as a market, rather than a base for manufacturing and research, is clearly outdated. Many Chinese firms invest in Europe to produce there.

These types of investments are particularly important for Chinese sectors that already have high levels of investment at home. Firms that invest a lot in production in China tend to do the same in Europe, potentially guaranteeing thousands of European jobs.

The role of the state

Given concerns about the role of the Chinese government in the economy and business, we also looked at whether we could see differences in investment behaviour in industries where the state has a stronger role.

We found that sectors where state-owned enterprises are more predominant tend to invest in manufacturing and research, while those in sectors identified as “encouraged industries” by the government (a varied group that includes textiles and civil satellites), are more likely to invest in sales.

So domestic government policy does seem to have an impact on the types of investment Chinese firms make in Europe.

We also looked in detail at how various characteristics of Chinese and European industries affected the types of investments made.

In more traditional established European industries and those with high growth rates, such as motor vehicles in the UK and Germany and chemicals in Hungary and the Netherlands, Chinese investors are more motivated by research and development than the market. Investments from high-tech Chinese sectors were more focused on both research and development and manufacturing.

Wine and robots

It is difficult to make generalisations about Chinese investors and why they invest in Europe. The wealthy individual buying a vineyard in France will have very different motivations to the company buying the key German producer of industrial robots.

Even within sectors, there are big differences. My previous workon Chinese investment in the French wine sector found that in some cases the investment was instrumental in moving the vineyards to new levels of growth and internationalisation, whereas in others there were significant cultural clashes and management difficulties.

In this varied context, it is difficult to make comprehensive judgements about the extent to which existing and future Chinese investments could be problematic going forward. What’s clear is that the more we know about these and other foreign investments in Europe, the better armed we are to decide whether and how to regulate them.