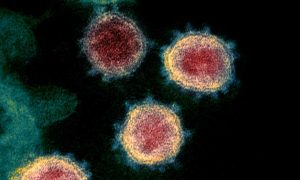

New study finds the white cells attack new Covid variant, offering protection and helping prevent significant illness

Human bodies have a second line of defence against Covid that offers hope in the global fight against the Omicron variant, Australian researchers say.

University of Melbourne research, done in conjunction with the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, has found T-cells should be able to tackle the virus.

Omicron has a higher number of mutations than other variants, which means it can sometimes slip past the antibodies produced by vaccination or infection. But if it does enter the body, the T-cells – white blood cells that originate in the marrow – will attack.

The research has just been published in the peer-reviewed journal Viruses.

Co-leader of the research, the University of Melbourne’s Matthew McKay, said while it was a preliminary study, it was “positive news”.

“Even if Omicron, or some other variant for that matter, can potentially escape antibodies, a robust T-cell response can still be expected to offer protection and help to prevent significant illness,” he said.

“These results overall would suggest that broad escape from T-cells is very unlikely.

“Based on our data, we anticipate that T-cell responses elicited by vaccines and boosters, for example, will continue to help protect against Omicron, as observed for other variants. We believe this presents some positive news in the global fight against Omicron.”

The team studied fragments of Covid’s viral proteins – called epitopes – from patients that had been vaccinated or infected.

Among the epitopes that had the Omicron mutation, more than half were predicted to still be visible to T-cells, HKUST research assistant professor and study co-lead Ahmed Abdul Quadeer said.

“This further diminishes the chance that Omicron may escape T-cells’ defences,” he said.

The paper’s authors warn that T-cell responses alone do not block infection and therefore prevent transmission. However, the T-cell immunity provides hope of a protection against severe disease.

Dr Stuart Turville, from the University of New South Wales’ Kirby Institute, has been studying samples from people infected with Omicron. He said T-cells represent a “pretty good backup” in the immune response.

That response is multi-factorial, he said, as both T-cells and B-cells (which produce antibodies) develop a “memory” of the virus that attacks the body.

“At the beginning, what gives them that memory is the primary encounter,” Turville said. “If you’re lucky, it’s a vaccination; if you’re unlucky, it’s the first time you’re infected.”

University of Sydney’s Prof Robert Booy, who is also a director of the Immunisation Coalition, said T-cells were an “important backup” to antibodies because they recognise different parts of viruses to produce a response to entire cells, not just their proteins.

Australia has a long history of T-cell research, he said. Prof Peter Doherty – the patron of the Peter Doherty Institute, which has been providing Covid modelling – won the Nobel prize in 1996 for his work on T-cell-mediated immunity.

Booy also pointed to world-first work being done at the Westmead Institute for Medical Research on how long-term immunity to Covid works, and the possibilities of a T-cell vaccine.

The new University of Melbourne research also adds to existing international work that shows the importance of T-cells.

South African researchers have found that T-cells can robustly protect against Omicron after it has evaded antibodies. A small South African study that has not yet been peer-reviewed also suggested T-cells have a role to play.