Analysis – Has Jacinda Ardern really faced more crises than other New Zealand prime ministers, or is she simply the leader in a time when rolling news and social media puts her centre stage?

Jacinda Ardern announces the attack at LynnMall was terrorism. Photo: POOL / Stuff / Robert Kitchin

Jacinda Ardern announces the attack at LynnMall was terrorism. Photo: POOL / Stuff / Robert Kitchin

Why are more things happening in the news right now, my daughter asked.

The daily dread of the 1pm Covid update is like a screensaver to my seven-year-old.

But now the prime minister was explaining that a terrorist, who had been on a watchlist for five years, was shot within minutes after a frenzied stabbing attack.

Friends and work colleagues were asking the same question on text and Microsoft Teams and Twitter. Two terror attacks, the Whakaari/White Island eruption and a global pandemic: Has a New Zealand prime minister ever dealt with what Jacinda Ardern is dealing with?

Sitting in a level 4 lockdown queue waiting to get my second vaccination on the day after an Isis-inspired terror attack seemed like a good place to contemplate this.

Like any interesting question it’s impossible to answer definitively. But my sense is that past prime ministers have faced events equally as challenging as those that confront Ardern.

What has changed dramatically is the nature of those challenges, our perception of them and what we expect of our leaders.

Asked by a journalist what troubled him most, Harold Macmillan, British Prime Minister between 1957 and 1963, famously replied, “events, dear boy, events”.

Leaders may have plans for grand transformation but these are often forgotten and they are instead judged by how they reacted to events along the way.

This is particularly true in New Zealand where many of the big economic and social questions that tore the country apart in the 1980s and 1990s, are largely settled, at least among the major parties.

For Helen Clark it was war in the Middle East. After the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, US President George Bush threw down an ultimatum: you are either with us, or you are with the terrorists.

Clark decided we were with the US and New Zealand troops went into Afghanistan. Less than two years later Clark stared down intense pressure from our traditional allies to resist joining the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Clark achieved plenty on the domestic front but those two crisis moments still resonate today.

For John Key it was navigating New Zealand’s economy through the Global Finance Crisis and dealing with the aftermath of the Christchurch earthquakes, which destroyed our second largest city and killed seven times the number of New Zealanders who have died from Covid-19 so far.

So that’s the first change: without the raging ideological debates of the 20th century our leaders tend to be defined by how they handle crisis, war or disaster.

The second change is what we expect our leaders to actually do.

In the past it was possible to lead without always being seen to lead.

The extreme example of that would be Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the president who steered America through the great depression and World War II.

Polio – that devastating epidemic of the 20th century – left him unable to walk unaided and he used a wheelchair in private. But the White House went to extraordinary lengths to conceal his disability from the public.

Even in recent New Zealand history we have not expected to watch our leaders carry us, moment by moment, through national tragedy.

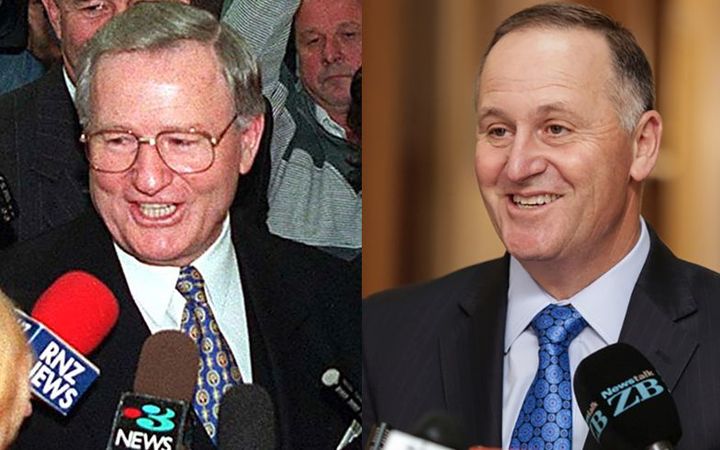

Jim Bolger, left, was at the helm for Cave Creek, while John Key, right, faced the GFC and the Christchurch earthquakes. Photo: AFP / RNZ

Jim Bolger, left, was at the helm for Cave Creek, while John Key, right, faced the GFC and the Christchurch earthquakes. Photo: AFP / RNZ

In April 1995 New Zealand was deeply shaken when 14 people lost their lives at Cave Creek, after a viewing platform collapsed in Paparoa National Park. But few would remember Prime Minister Jim Bolger as the face of the Cave Creek tragedy in the way we might assign that role to Ardern in the wake of 22 deaths in the Whakaari eruption of December 2019.

In an age of instant, ubiquitous and non-stop media we look on a prime minister as a kind of Communicator-in-Chief. It’s a role that Ardern is highly skilled at.

Technically, a prime minister chairs the Cabinet which collectively makes decisions based on expert advice from politically neutral public servants and so is just one of many decision makers in the Covid-19 response.

In reality we watch Ardern every day communicating that response with a great deal of skill, and the effect of that is a feeling that ‘she is dealing with Covid-19’. When the next minute she is at the podium telling us a terrorist has stabbed shoppers at an Auckland supermarket, we think – what will she face next?

Has a prime minister ever dealt with the events Jacinda Adern is dealing with? Yes, they probably have, but maybe you weren’t locked in your house for days on end watching them respond.