Students will submit work related to China anonymously and told not to record classes

Students at Oxford University specialising in the study of China are being asked to submit some papers anonymously to protect them from the possibility of retribution under the sweeping new security law introduced three months ago in Hong Kong.The anonymity ruling is to be applied in classes, and group tutorials are to be replaced by one-to-ones. Students are also to be warned it will be viewed as a disciplinary offence if they tape classes or share them with outside groups.

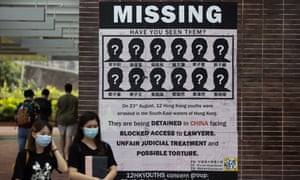

The Hong Kong security law was imposed on 30 June by Beijing after more than a year of pro-democracy protests, and had an immediately corrosive impact on political freedoms in the territory. Its provisions also give the Chinese government powers to arrest individuals who are not Hong Kong residents, for actions or comments made outside the territory.

The powerful extraterritorial powers claimed in the law have led to fears for those studying in the UK, in particular for those with personal and family connections to Hong Kong and mainland China.

Universities UK, the vice-chancellors’ group, is to hold talks with Chinese scholars to discuss the national security law early next month. A group of academics are also expected to advance a draft code of conduct this week for how universities should deal students from authoritarian states.

The number of Chinese students in UK higher education has grown by more than a third in the past four years and is now above 120,000.

In 2018-19, 35% of all non-EU students were from China. Numbers are due to rise again this year, but the full impact of the Covid-19 pandemic is not yet known.

Overseas students are a valuable source of income for the UK university sector since they often pay two to three times as much in fees as UK students.

Patricia Thornton, associate professor of Chinese politics at Oxford University, said: “The entire spirit of the tutorial, which rests on collective critical inquiry, rises or falls on the ability of the institution to guarantee free speech, freedom of expression and academic freedom for all.

“But how to do this in the wake of China’s new national security law for Hong Kong, which invites self-censorship with its lack of red lines and generous extraterritorial provision? How does one protect academic freedom when China claims the right to intervene everywhere?”

She said: “I have decided not to alter the content of my teaching. However, like my colleagues in the US, I am mindful of my duty of care for my students, many of whom are not UK citizens. My students will be submitting and presenting work anonymously in order to afford some extra protection.”

Her students will be asked to read anonymised papers in weekly classes, and small group tutorials will be replaced by one-on-one lessons. “This means my lectures, reading lists and tutorial essay questions will remain largely the same, but the students will be asked to present the anonymised work of one of their peers in classes.”

She said advice is being issued that if classes are delivered online, there must be no attempt to record the content or share the material with anyone outside the group.