Analysis: New Zealanders’ intention to get a Covid-19 vaccine is at its highest since last year, at 81 percent of the adult population, according to our latest research.

Photo: AFP

Photo: AFP

Ministry of Health surveys, which have been tracking public acceptance of Covid-19 vaccines since last year, also confirm the potential uptake has increased to 80 percent in May, up from 77 percent in April and 69 percent in March this year.

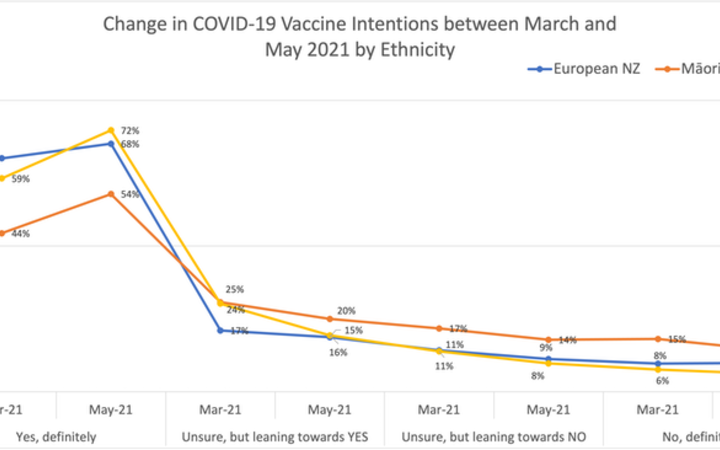

Our longitudinal survey, conducted between March and May, shows an increase by six percentage points among those who will “definitely” take the vaccine to protect themselves and their communities, to 67 percent in May compared to 61 percent in March.

The increase is visible across gender, age, education and ethnicity. Among Māori, we see a 10 percent increase among those “definitely” willing to be vaccinated, from 44 percent in March to 54 percent in May.

However, the number of people who say “definitely not” to vaccination remains relatively steady, dropping only slightly to 8 percent in May, from 9 percent in March.

The uptick in vaccination intentions is good news, but recent modelling suggests we will need to reach much higher vaccination rates to protect the population from the more transmissible Delta strain.

Photo: THE CONVERSATION/ Jagadish Thaker

Photo: THE CONVERSATION/ Jagadish Thaker

Of the survey respondents, fewer than a third (27 percent) have often or very often heard or read the government’s Covid-19 vaccination communication campaign on the radio, in newspapers or on social media in the last month. About four in ten people (43 percent) have often or very often heard about the campaign on television.

This lack of exposure is worrying. When we asked people who are hesitant or sceptical about vaccination what information they would need to change their mind, 30 percent said they’d want more information from the government. This is a substantial increase from 18 percent in March and suggests a low campaign reach.

The most frequently cited information request was for more vaccine safety data. This remained at 30 percent between March and May. In contrast, there was a sharp decline in the need to see other people take the vaccine first, from 21 percent in March to 8 percent in May.

Drop in Covid-19 safety behaviours

We also surveyed participants about the measures they take to protect themselves. The largest decline we observed was in mask wearing, from 64 percent in March who always, often or sometimes wore a mask in public to 50 percent in May.

More than three in four respondents continue to use the contact tracing app, down slightly from 78 percent in March to 76 percent in May, but encouraging others to use the app has declined from 73 percent to 66 percent.

The World Health Organization (WHO) advises even fully vaccinated people should continue to follow Covid-19 safety behaviours, such as wearing masks in public places.

Misinformation continues to influence people’s decisions, but campaigns to correct it appear to have an impact.

Of the people who watched a misinformation correction video, featuring Auckland GP and advocate for Māori health Rawiri Jansen, 66 percent said they would definitely take the vaccine, compared to 62 percent who watched a misinformation videopopular among vaccine sceptics on social media channels. The order of watching misinformation and correction does not seem to matter.

The effect of watching a misinformation correction video (just once) appears small, but it highlights the need for continued communication campaigns to address misinformation about the safety, efficacy and regulatory approval of Covid-19 vaccines.

Challenges for the vaccination programme

In several countries, vaccination rates have stalled after an initial uptick.

In the UK, vaccination rates have reduced by 50 percent recently, primarily due to lack of enthusiasm among the young. In the US, vaccination rates fell just short of President Biden’s target of getting at least 70 percent of the adult population partly vaccinated before Independence Day on 4 July.

Worryingly, the vaccination rates are uneven between US states, and nearly all Americans dying of Covid-19 are unvaccinated.

This has led Biden to launch a “wartime effort” to vaccinate the country, including door-to-door outreach, vaccination clinics at workplaces, and urging employers to offer paid time off.

Some US states have offered scholarships, million-dollar lottery tickets, free beers and even shotguns as incentives to increase the vaccination rate.

New Zealand is likely to face similar hurdles. While it may be easier to motivate some hesitant people by improving vaccine access and providing services such as paid leave, it will be difficult to reach those with high distrust in government and health experts.

Communities that have been neglected in conversations about health policies may see the vaccination effort more as a benefit to the government rather than a concern for their own and their community’s well-being. Placing vaccination campaigns with trusted community members will help, as we have seen when more than 1000 Pacific people turned up to be vaccinated when the clinic was organised with help from their community and held at their church.