Analysis – What is New Zealand’s most important role in a quickly changing geopolitical world? It could be mediating between China and the West.

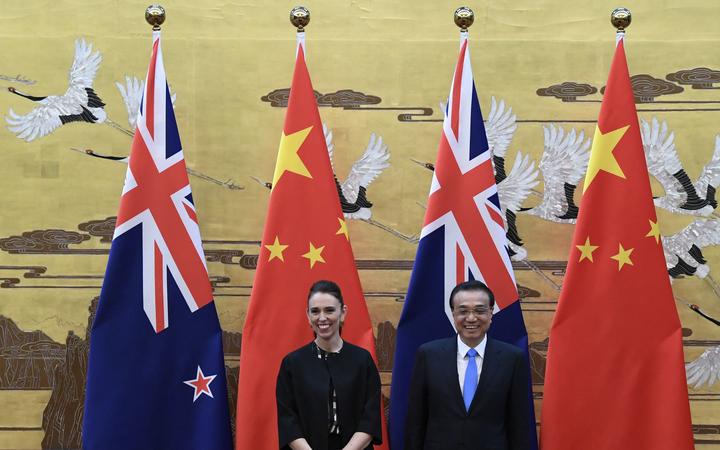

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern (left) and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on 1 April 2019. Photo: AFP

A keynote speech by Jacinda Ardern next week will set the tone for a busy few months of foreign policy activity, culminating in New Zealand’s virtual hosting of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) leaders’ summit in November.

The coming months also include the annual meeting of the UN General Assembly in New York in September and the COP26 climate change summit, to be held in Glasgow in late October and early November.

Ardern made high-profile visits to the UN in her first two years in office – in 2018 and 2019. Her plans for this year have not yet been announced.

Ardern will address the New Zealand Institute of International Affairs (NZIIA) conference – Standing in the Future: New Zealand and the Indo-Pacific Region – in Wellington on Wednesday.

She is once again likely to address the ongoing tensions between China and the West.

Ardern’s speech will be immediately followed by a virtual appearance by Kurt Campbell, a top official in Joe Biden’s administration widely seen as one of the original architects of the US’ renewed interest in the Asia-Pacific.

Campbell is almost certain to use his speaking slot as an opportunity to give New Zealand the hard sell on why it should be siding with Australia and the US.

The US and its allies are increasingly using the phrase “free and open Indo-Pacific”, a term that originated in Japan, to sum up their alternative vision to growing Chinese influence.

The “free and open” language partly refers to freedom of navigation, especially in relation to the disputed South China Sea. But it is also used to signal wider discontent with China’s actions elsewhere.

These range from everything from the suppression of pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, to what are perceived to be underhand trade tactics – such as the tariffs China imposed on Australia last year after Scott Morrison called for an investigation into the origins of Covid-19.

The fiercely competing approaches now being advanced by Washington and Beijing are in stark contrast to the once cooperative spirit of the APEC grouping that counts China and the US amongst its members.

This year is New Zealand’s turn to host high-level meetings for the 21-member grouping. While the main public focus is on the leaders’ summit in November, APEC also involves a series of meetings between finance ministers and other officials throughout the year.

Amongst APEC’s members are major world powers such as China, Japan, Russia and the United States – as well as much smaller countries such as New Zealand.

The only real commonality amongst members is their location on the Pacific Rim.

APEC makes no distinction over wealth or form of government. The grouping includes Papua New Guinea – where nearly 40 percent of the population lives on under $US2 a day – and oil-rich Brunei, one of the world’s richest nations.

Democracies and authoritarian regimes alike are welcomed under the APEC umbrella.

And unusually, APEC includes both China and Taiwan, whose differences explain why APEC members are officially only ever referred to as “economies”, rather than countries.

But in a sense, APEC – founded in 1989 – is a throwback to a more optimistic period at the end of the Cold War, when increased multilateral cooperation seemed like it would be the way of the future.

China’s accession to APEC in 1991 – along with Russia’s entry in 1998 – seemed to be confirmation of APEC’s early promise.

Three decades on, the picture looks very different.

Even APEC’s very name – with “Asia Pacific” – appears to be outdated, amidst a Western push to rename the region the “Indo-Pacific” in a bid to de-emphasise China’s centrality.

The tide seems to be going out on broad-based, multilateral cooperation, in favour of smaller, more ideologically-driven arrangements, such as the Five Eyes.

But as Professor Robert Patman pointed out at last weekend’s Otago Foreign Policy School in Dunedin, this trend away from what scholars call an “rules-based order” to one dominated by raw state power is unlikely to end well for a small trading nation such as New Zealand.

New Zealand’s commitment to multilateralism dates back to its role as a founding member of the UN in 1945, when it unsuccessfully opposed giving the five permanent members of the Security Council – China, France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States – a right of veto.

More recent examples include a host of trade arrangements that New Zealand has joined, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the AANZFTA deal which links Australia and New Zealand with the ten-country ASEAN group in Southeast Asia.

Indeed, Southeast Asia’s place in the rules-based system was the subject of much discussion at a roundtable hosted by the Asia New Zealand Foundation on the sidelines of the recent Otago event.

Smaller Southeast Asian countries – dwarfed by China – share some similarities with New Zealand in their appreciation of the benefits of multilateral arrangements. Singapore and Brunei joined NZ and Chile to form the original P4 grouping in 2005 that eventually became the CPTPP.

With the tide seemingly going out on multilateral arrangements, is it time for new approaches?

One potential solution to the growing tensions between China and the West was put forward at the Otago Foreign Policy School by Reuben Steff, a former New Zealand diplomat now lecturing at the University of Waikato.

Steff sets out an alternative model under which New Zealand would effectively play the role of mediator, nudging both sides to make concessions.

The plan would involve New Zealand establishing a new research centre focusing on “Great Power Competition”, but would also see New Zealand facilitating and providing a venue for “confidence building” talks between Beijing and Washington.

The Waitangi Trust Treaty Grounds are suggested by Steff as a potential venue for holding the talks.

While the idea might seem fanciful given the rising tensions – and New Zealand has relatively little experience as a diplomatic go-between – in some ways it is ideally placed to mediate between China and the West.

Lessons could also be drawn from Switzerland’s recent hosting of a summit between Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin, which was arranged to deescalate tensions amidst a round of sabre-rattling on the Ukraine-Russia border earlier this year.

Could New Zealand play the role of Switzerland when it comes to China?

Potentially.

It is difficult to find another Western country that has a better relationship with Beijing than New Zealand.

Yet Wellington is also still largely on-side with key Western partners – despite inevitable murmurings of discontent over New Zealand’s China strategy.

Foreign minister Nanaia Mahuta’s emphasis of an indigenous approach to foreign policy that draws on traditional Māori values could also be a valuable asset.

New Zealand’s success in helping to resolve the Bougainville conflict in the 1990s has in part been attributed to the role that Māori protocol played both in peacekeeping operations and in the negotiations that were held near Christchurch in 1997 and 1998.

New Zealand’s hosting of the APEC leaders’ summit in November – which will bring Xi Jinping, Joe Biden and Scott Morrison together, albeit in virtual form – could at least provide a starting point for thinking about some form of rapprochement.

A chance to break the ice – via Zoom.