Skeleton found by children in New Zealand helps fill in gaps in natural history

In January 2006 a group of children in summer camp in Waikato, New Zealand, went on a fossil-hunting field trip with a seasoned archaeologist. They kayaked to the upper Kawhia harbour, a hotspot for this sort of activity, and they expected to find fossils of shellfish and the like, as they regularly did on these Hamilton junior naturalist club expeditions.

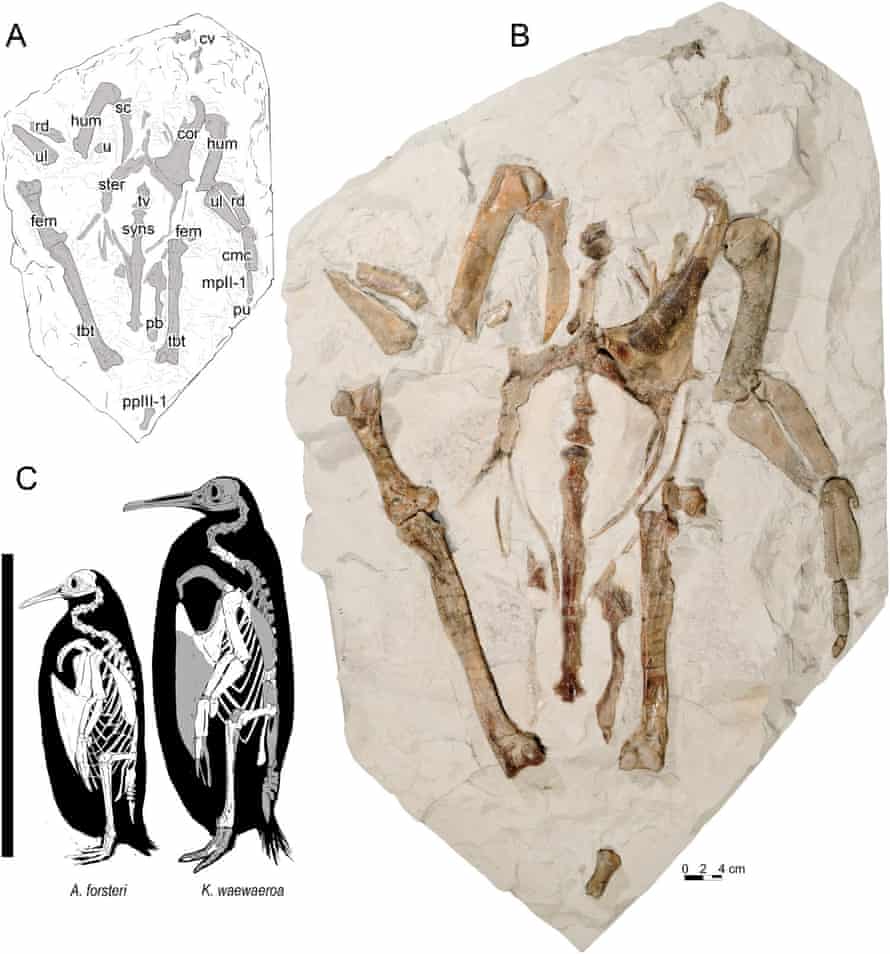

But on this day, just before heading home, close to where they’d left the kayaks and well below the high tide mark, they noticed a trace of fossils that looked like much more than prehistoric crustaceans. After careful extraction, an archaeologist later identified it as the most complete fossilised skeleton of an ancient giant penguin yet uncovered.

According to a study newly published in the Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology by Massey University scientists, it was a new species of prehistoric penguin. The discovery is helping scientists fill in some gaps in natural history. Penguin species have a fossil record dating almost as far back as the age of the dinosaurs and can say a lot about the ecology of the past and the present.

“Finding fossils near where we live reminds us that we share our environment with animals who are the descendants of lineages that reach back into deep time,” said Mike Safey, the Hamilton junior naturalist club’s president, who has overseen all work on the fossil penguin since its discovery. “We should act as kaitiaki – guardians – for these descendants if we want to see these lineages continue into the future.”

A month after the discovery the team returned to the location with equipment ranging from petrol-powered concrete saws and electric jackhammers to chisels and crowbars, and children and adults alike spent a day cutting the fossil out of the sandstones. It was donated to the Waikato Museum, Te Whare Taonga o Waikato, and researchers from Massey University and Bruce Museum started to conduct cutting-edge studies on the fossil.

The scientists concluded that the penguin is between 27.3 and 34.6m years old and is from a time when much of Waikato was under water, according to Daniel Thomas, a senior lecturer in zoology from Massey’s School of Natural and Computational Sciences.

“The penguin is similar to the Kairuku giant penguinsfirst described but has much longer legs,” Thomas said. That’s why it’s been called waewaeroa, which is Māori for “long legs”. Having legs this long would have made this species much taller than other ancient giant penguins, and it is estimated that it was about 1.6 metres long from toe to beak tip and 1.4 metres tall when standing up. This, in turn, would affect how fast it could swim and how deep it could dive.

“Giant penguins like Kairuku waewaeroa are much larger than any diving seabird today, and we know that body size can be an important factor when thinking about ecology,” Safey said. “How and why did penguins become giant, and why aren’t there any giants left? Well-preserved fossils like this can help us address these questions.”

Little is known about the existence of giant penguins in New Zealand, especially since records from the North Island have long been limited to a few fragmentary specimens. So adding this new information to the rich fossil record of penguins provides insight into how penguins adapted, and the evolution of the art of adaptation itself.

Discovering that this fossil penguin is a new species was also rewarding for the children of the Hamilton junior naturalist club, and will encourage other young people to connect with nature.

Steffan Safey was 13 at the time of the discovery. “It’s sort of surreal to know that a discovery we made as kids so many years ago is contributing to academia today. And it’s a new species even,” Safey said.