Contrary to corporate media narratives, up to 95 percent of this summer’s riots are linked to Black Lives Matter activism, according to data collected by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). The data also show that nearly 6 percent — or more than 1 in 20 — of U.S. protests between May 26 and Sept. 5 involved rioting, looting, and similar violence, including 47 fatalities.

ACLED is a nonprofit organization that tracks conflict across the globe. Its U.S. project that collected the summer protest data is supported by Princeton University. The project’s spreadsheet collating tens of thousands of data points documents 12,045 incidents of U.S. civil unrest from May 26, 2020 to Sept. 5, 2020. May 26 is the day after George Floyd’s death in police custody with enough fentanyl in his system to have died of an overdose if police had never touched him.

Of the 633 incidents coded as riots, 88 percent are recorded as involving Black Lives Matter activists. Data for 51 incidents lack information about the perpetrators’ identities. BLM activists were involved in 95 percent of the riots for which there is information about the perpetrators’ affiliation.

Early estimates from insurance agencies say the cost of this summer’s rioting will set a record surpassing that of the 1992 Rodney King riots, which cost an inflation-adjusted $1.2 billion. Much of that will be paid by taxpayers in the form of overtime and hazard pay for police and EMTs, emergency room visits, destruction of public property, and more. Of course, rioters are inflicting these costs during a time governments, and the people who fund them, have fewer resources due to coronavirus shutdowns and pent-up entitlement obligations.

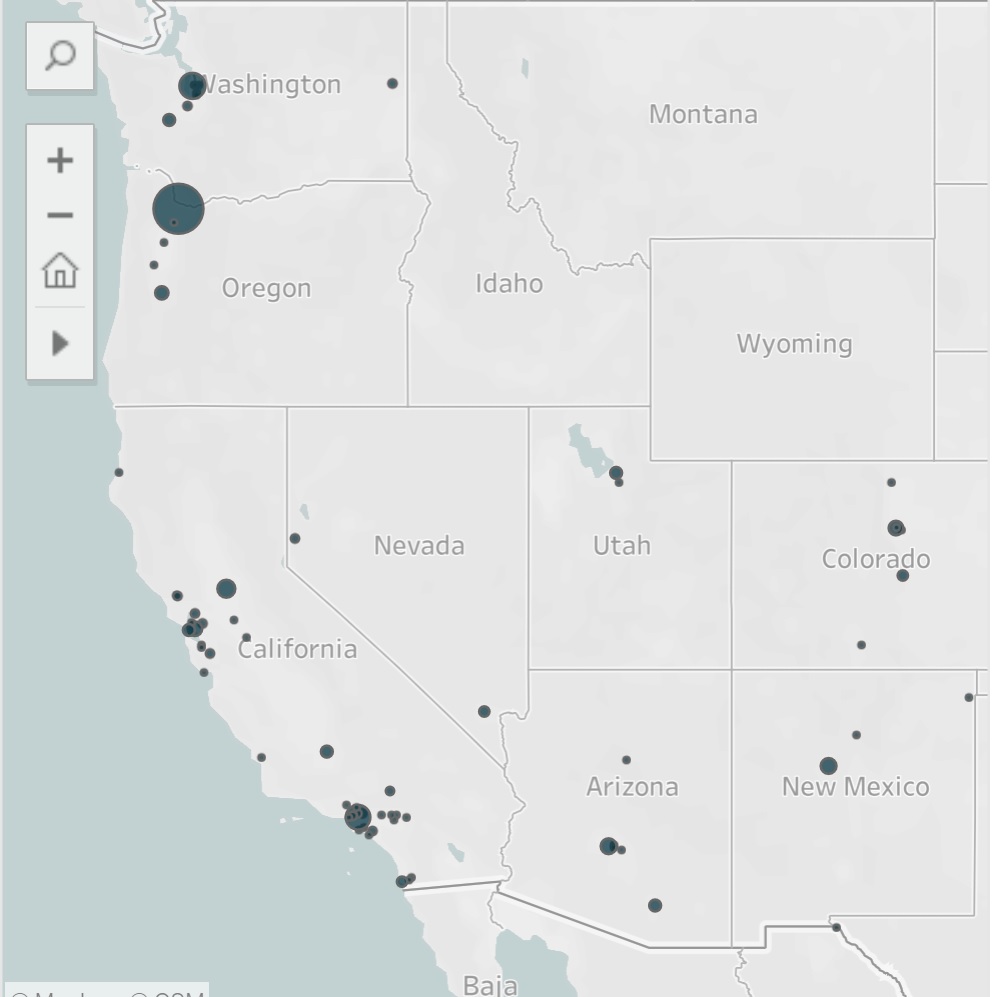

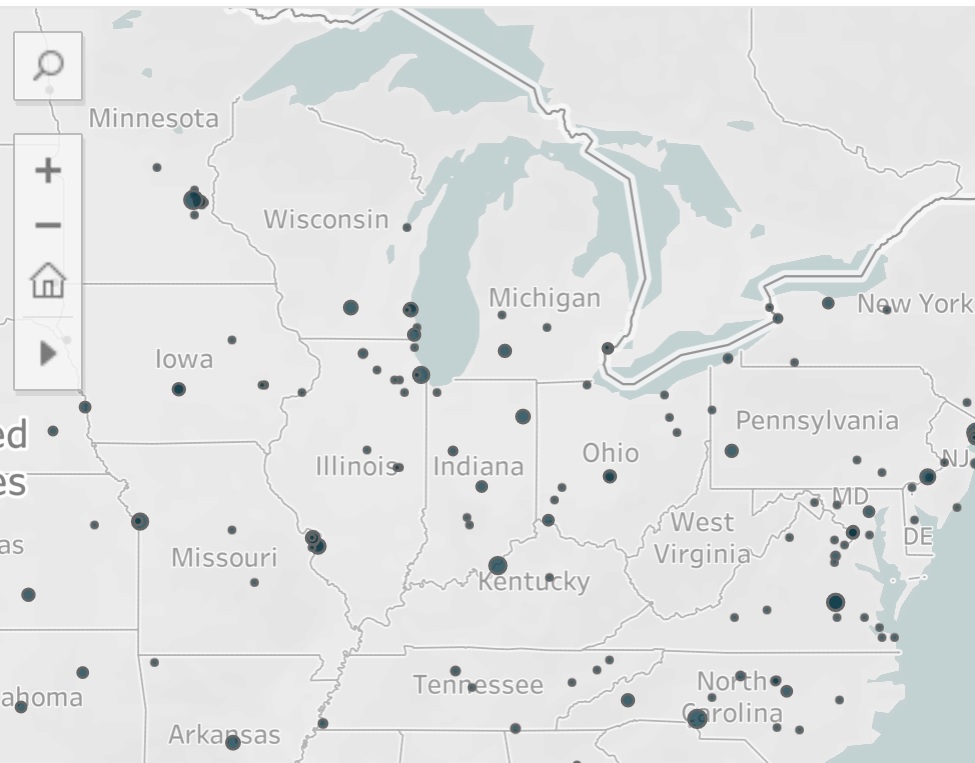

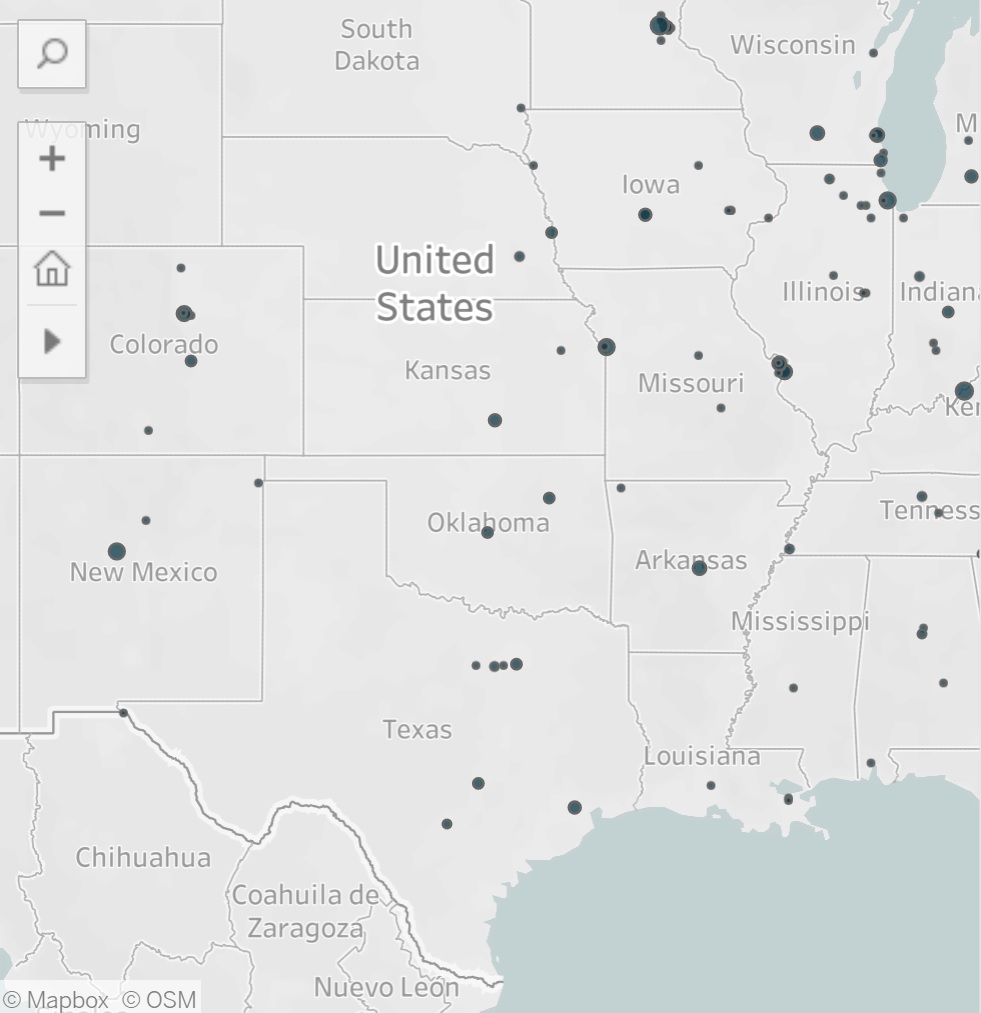

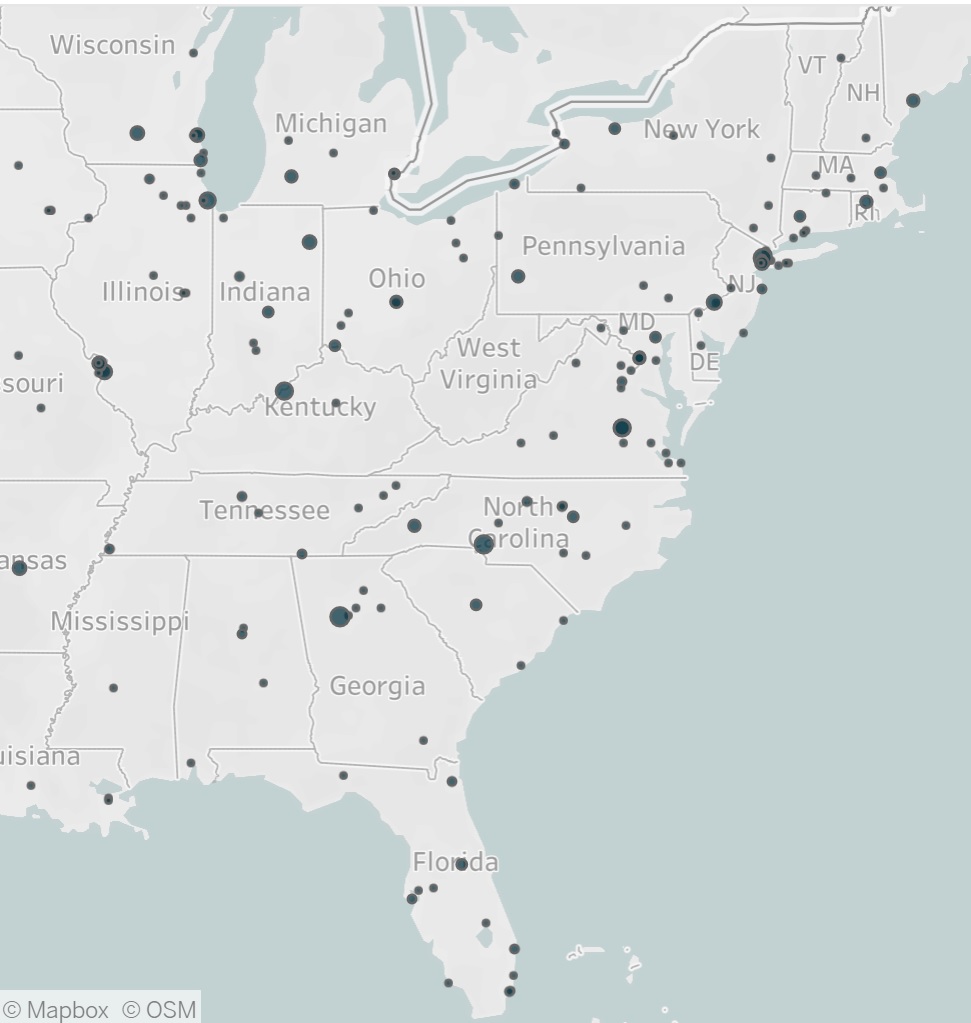

A look at an interactive map illustrating the data shows just how widespread the summer BLM-linked rioting has been. It has not been limited merely to anarchist strongholds such as Portland, Oregon, or locales that saw media-spotlighted violent interactions between police and suspects, but has stretched across both major and minor U.S. cities and included dozens of locales with no violent police incidents this summer.

Here are some screenshots of the map. The circle size indicates the number of riots.

West Coast Riot Locations

Midwest Riot Locations

Central U.S. Riot Locations

Midwest/Mid East Coast Riot Locations

A report accompanying the data project, however, reads like an upscale attempt to blame the police for criminals’ decision to steal, kill, and destroy. Several times the report explicitly does so, such as here: “Although federal authorities were purportedly deployed to keep the peace, the move appears to have re-escalated tensions. Prior to the deployment, over 83% of demonstrations in Oregon were non-violent. Post-deployment, the percentage of violent demonstrations has risen from under 17% to over 42% (see graph below), suggesting that the federal response has only aggravated unrest.”

This is a logical fallacy called post hoc, ergo propter hoc: Because one thing happened after another, the first thing caused the second. It’s just plain false. In science, this error is described as the difference between correlation and causation. Social scientists ought to be aware of and refrain from employing it, yet these did not.

The cause of violence is not the police. It is not poverty. It is not one’s race. To say so is in fact a smear against poor people and people of the racial group identified. The cause of violence is the people who have chosen to be violent.

Rather than assigning responsibility for violence to those who engage in it, the report constantly pushes the criminal victimization narrative that the rioters are not to blame for their rioting. This is abuser psychology 101: The abuser is never responsible for his or her abuse. The people who might object to it are. This is also false and manipulative.

The report also attempts to downplay the wave of BLM-linked violence sweeping the nation this summer, even while documenting it.

“The vast majority of demonstration events associated with the BLM movement are non-violent (see map below). In more than 93% of all demonstrations connected to the movement, demonstrators have not engaged in violence or destructive activity,” it states. “Peaceful protests are reported in over 2,400 distinct locations around the country. Violent demonstrations, meanwhile, have been limited to fewer than 220 locations — under 10% of the areas that experienced peaceful protests.”

I’m sure it is comforting to those whose businesses have been burned down and insurance won’t cover it to hear that the movement that ruined their livelihoods protests peacefully in most other cities.

ACLED labels a 5 percent rate of police use of “force” — such as rubber bullets, tear gas, pepper spray, and other crowd dispersal techniques — as “heavy handed.” Thus ACLED both claims a 6 percent rate of rioting is “peaceful” and “non-violent” and that a 5 percent rate of police response to such riots is “heavy handed.”

“Over 5% of all events linked to the BLM movement have been met with force by authorities, compared to under 1% of all other demonstrations,” its report says. Elsewhere, it says: “ACLED conducted a pilot data collection program for the US last summer, allowing for comparison of the current moment with the same time period last year. In July of this year alone, ACLED records nearly 2,000 demonstrations — an increase of 42% from the 1,400 demonstrations recorded in July 2019.”

The violence is not limited to the extreme of rioting. It is pervasive in the summer 2020 protests. Of the 12,045 incidents recorded by ACLED, 1,143 — or nearly 1 in 10 — involved violence of some sort: rioting, looting, clashes with police, cars rammed into crowds, bystanders pepper-sprayed, armed attacks. Of these violent incidents, 84 percent involved BLM.

These statistics could be interpreted as indicating BLM is unusually violent among U.S. political movements, but ACLED interprets it in a way that enables resentment against police. Widespread U.S. political demonstrations such as the Tea Party, however, almost never featured violence despite holding thousands of events. Tea Partiers were even known for cleaning up the public areas where they demonstrated.

The report goes on amazingly to suggest that police standing behind barricades using tear gas and rubber bullets is a disproportionate use of force against rioting in Portland that has included the use of blinding lasers, rushes at barricades with clubs, destruction of public buildings, bomb-throwing, arson, and murder: “In some contexts, like Seattle, Washington and Portland, Oregon (see below), the heavy-handed police response appears to have inflamed tensions and increased the risk of violent escalation,” the ACLED report says.

Judge for yourself whether police use of force and riot-dispersal techniques often seems justified by reading the project’s summaries of some of these riots based on largely local news reports. I picked incidents from smaller cities to avoid the most sensational and nationally publicized instances, in an effort to fairly illustrate what police were responding to. The italicized material below is all quoted directly from the project. The bold is added.

On 28 May 2020, about 200-400 people demonstrated in Columbus, Ohio in support of the Black Lives Matter movement and against police brutality and the death of George Floyd. The demonstration turned violent when businesses and the Ohio Statehouse were damaged. Some people threw water bottles, smoke bombs, and other items at police. Police used tear gas on the demonstrators.

On 28 May 2020, around 400 people held a demonstration in Albuquerque, New Mexico over the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police. At night, the demonstration turned violent when a group of rioters were approaching vehicles and trying to damage them. Also, several shots were fired from a car and 4 people were arrested. Another man took a baseball bat and started smashing police car’s windows. Police used gas to disperse the crowd and control the area.

On 29 May 2020, hundreds of people attended a demonstration in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in support of the Black Lives Matter movement and against the death of George Floyd. The demonstration was initially peaceful until conflicts broke out between the demonstrators and the police. A demonstrator was pepper-sprayed twice in the face. Another demonstrator was shoved to the ground. Vandalism was reported. 29 people were arrested. Clashes continued until the next morning.

On 29 May 2020, over 1000 demonstrations [sic] were held in Des Moines, Iowa over the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police. Police vehicles and buildings were damaged. Police used pepper spray and tear gas and made 12 arrests.

On 30 May 2020, people demonstrated in Grand Rapids (Michigan) in support of the Black Lives Matter movement and against police brutality and the death of George Floyd. Rioters smashed windows and lit fires. A non-violent demonstrator was pepper-sprayed and shot in the face with a ‘Spede-Heat’ round by a police officer.

See the descriptions and locations of every riot recorded in the “Details of Events” box here.

According to many innocent victims of this wave of injustice, the police response is not robust enough. They want to know why the police are not protecting them and their property. They pay taxes. They contribute to the common good rather than attempt to destroy it. What’s the point of mayors and governors if they don’t ensure their police protect innocent people and their property when rioters come to town?