Tiwai Point aluminium smelter has doubled its clean-up costs to almost $700m, and documents show one reason is that getting rid of the most toxic of its waste is far from plain sailing.

File photo: Tiwai Point aluminium smelter Photo: Otago Daily Times / Stephen Jaquiery

File photo: Tiwai Point aluminium smelter Photo: Otago Daily Times / Stephen Jaquiery

They show the company last year was pleading it was “desperate” to get exporting under way of the nastiest of its waste, spent cell lining or SCL, which is laced with toxic fluoride and cyanide.

It had a lack of storage space and asked repeatedly for the Environmental Protection Authority to move faster on helping it get a permit to ship the SCL offshore.

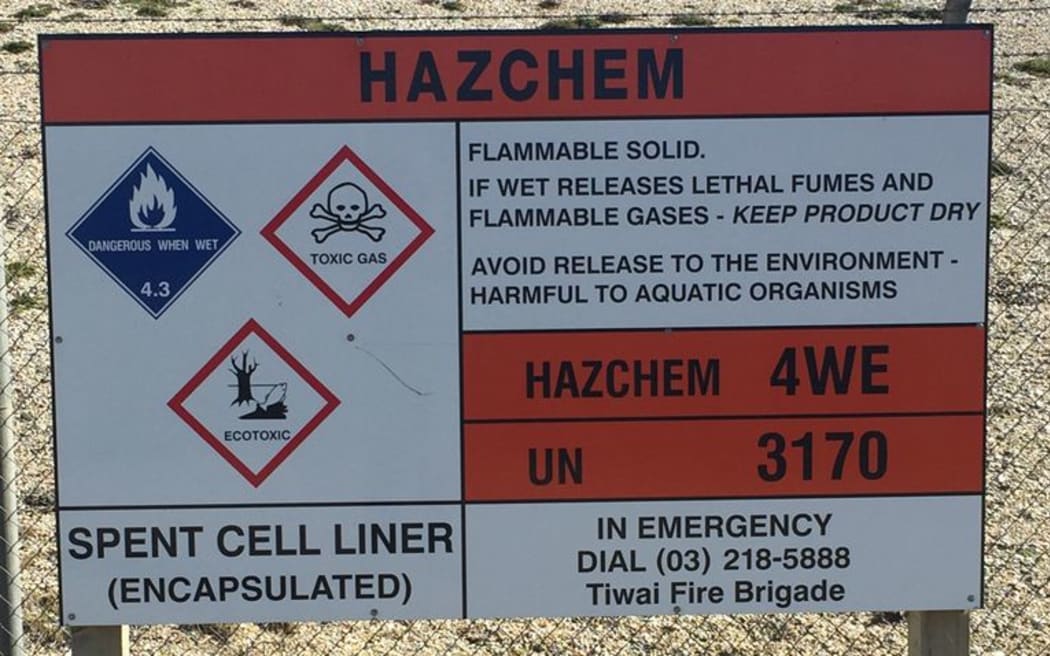

A small mountain of the waste – under a cover – remains beside the beach by Foveaux Strait, a short sprint to the ocean, behind a Hazchem sign warning: “If wet releases lethal fumes and flammable gases. Avoid release to the environment. Harmful to aquatic organisms.”

The rest was being dumped into sheds at the plant.

“We have a backlog of material that we are wishing to expedite urgently,” the company, New Zealand Aluminium Smelter (NZAS), told the authority in September 2021.

It took months more for it to be allowed to.

A hazchem sign by a SCL pad at the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter. Photo: Supplied

A hazchem sign by a SCL pad at the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter. Photo: Supplied

The smelter recently promised to remove all its SCL by 2029. This, the company said, depends on upping its removal rate fivefold, from just 5000-6000 tonnes a year to 30,0000-40,000 tonnes.

But can it achieve that?

Exporting is vital, and the documents – mostly emails – released under the OIA show just how hard that can be.

A smelter manager left a voicemail with the EPA in October 2021, and the OIA transcribed it:

“Just wondering if we can um [sic] discuss about how long it’s going to take and if you can accelerate it? Really nervous about getting this approved by the other countries before the end of the year.

“Um, as I said in my email to (redacted), which forms part of the commitments that our chief executive has made to um Minister Parker and um Prime Minister when this is over, so would really like to get this pushed through so we can start exporting.”

Those “commitments” were made after months of wrangling last year, during which ministers rebuked the smelter’s majority owner Rio Tinto for not doing more to reveal how dirty the site is, and ensure funding for a proper clean-up.

Rio Tinto later changed tack, and one result was this week’s announcement that it had lifted its provision for clean-up and closure to $687m, up from $352m.

The closure costs may be some way off; the smelter looks increasingly unlikely to be shut in December 2024 after all.

However, the clean-up costs will only rise, for just as long as the smelter keeps generating more SCL and other waste, into 2025 and beyond.

“We will remediate the site, whether we stay beyond 2024 or not,” the smelter has pledged.

It already has 220,000 tonnes of spent cell lining waste stored.

SCL is a contaminated coating regularly scraped out of the pods used to make aluminium.

It is more toxic than the dross and ouvea mix that posed a threat at Mataura, which has since been moved back to Tiwai Pt.

The company took three goes last year to get the amount of SCL waste it had right: First it told RNZ it had 106,000 tonnes of SCL; then 181,000 tonnes; and finally, 217,000 tonnes.

The smelter has filled to capacity a big concrete pad 80m from the beach – a replacement for one that cracked and leaked pollutants into Foveaux Strait in the 1990s – and is filling up four sheds.

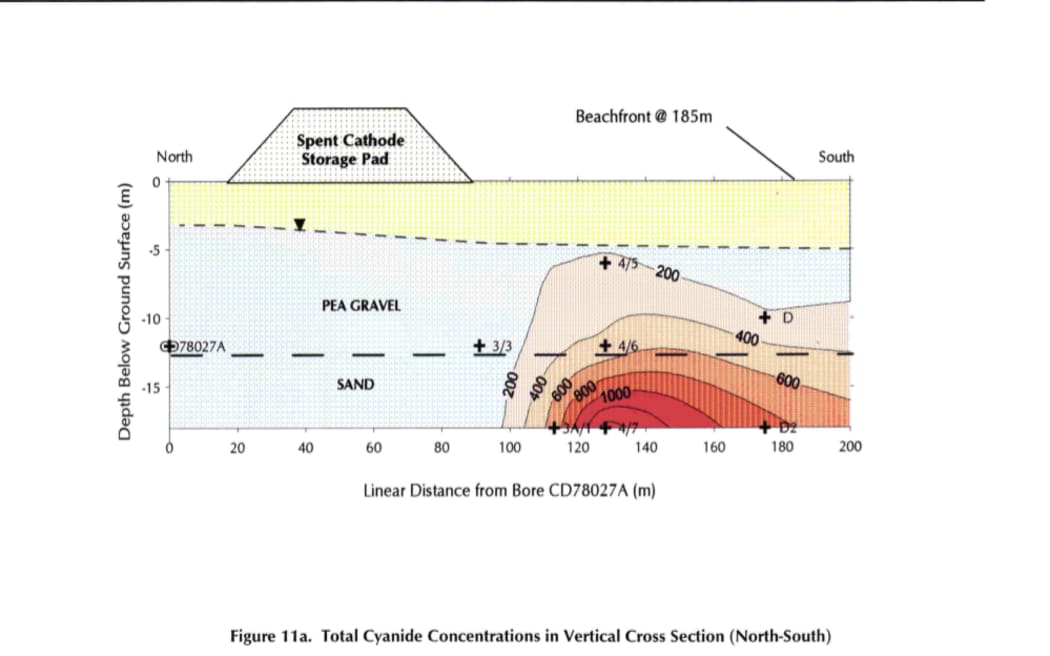

Cross section of the cyanide plume heading towards the beach (to right) from a pad at the top, in the mid 1990s, after the pad cracked. Erosion has since reduced the 185m to the beachfront by about half. Photo: Supplied / NZAS

Cross section of the cyanide plume heading towards the beach (to right) from a pad at the top, in the mid 1990s, after the pad cracked. Erosion has since reduced the 185m to the beachfront by about half. Photo: Supplied / NZAS

On top of that, industry data suggests the smelter generates about 8000 tonnes of SCL a year, from aluminium production of about 330,000 tonnes.

The plant is by the beach in a coastal management zone overseen by Environment Southland, close to a taonga wetland and opposite Bluff.

The promise to remove all the stored and new SCL by 2029 depends on exporting it to recyclers abroad (for the cement and salt slag industries), while at the same time setting up a recycling plant here.

“NZAS has launched projects to accelerate the removal of SCL and dross as an operational priority independent of the closure date. In both cases, acceleration is via a combination of direct export and on-site treatment processes,” NZAS said.

Setting up a local plant could be difficult.

The OIA emails show the smelter has been in talks with a company – its name is blanked out – that is recycling SCL in Australia, and which might do the same here.

But first, NZAS sought advice from the Environmental Protection Authority on what it would take to “prove that the transformed material is no longer hazardous and can be exported as a product”, a July 2021 email said.

Australia’s consenting authority had approved it under the Basel Convention on chemicals, and “as one of the key outputs from our due diligence, we would expect that would obtain a similar ruling from the NZ EPA”, NZAS said.

The company declined to comment to RNZ on where that had got up to, or on the exporting of SCL.

Conservative estimates are it costs $1000 to deal with each tonne of the hazardous waste.

Since it is hazardous, exporting it is tricky, and becoming more and more difficult, as the company has acknowledged to RNZ before, with each shipment needing a signed-off permit from every single port a ship goes through.

The emails reveal just how tricky that is.

‘Lack of storage space’

The smelter had managed to export 58,000 tonnes, mostly to Europe, up to early 2021.

But storage was filling up and in June last year efforts began to export more to recyclers in central Spain.

Despite the urgency expressed, though, the smelter took repeated attempts over several months to get its paperwork in order for the EPA.

Its application initially said it was for export to England, instead of Spain, then another mistake when it provided copies of quality standard certifications that had expired, the emails show.

NZAS was seeking a permit covering three years and 1200 containers, a total of 30,000 tonnes (so, a third of what it aims to remove every year to hit the 2029 deadline).

The cost to deal with just this lot is $7.3m, according to NZAS where it tells Spanish authorities: “The processing cost of recovery to the exporter is 153 euros/tonne.”

But hazardous waste watchdogs in Egypt, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Italy, Australia, Malaysia, and Malta, where the shipments would pass through, each came back with different approval periods, of as little as one year.

The smelter appeared ready to push the envelope. In July 2021, NZAS asked a logjammed EPA:

“Is it sufficient that we have already provided the Insurance Certificates of Currency and letter from Insurance Broker? I am afraid that waiting on the full policy will delay this permit approval further and we are in a real need to start exporting this product ASAP due to lack of storage space.”

In August, a problem arose with the Spanish recycler not having registered with the OECD.

“Befesa were not aware they had to do this,” the smelter said. “Can this still be progressed given the approvals that Spain has provided?”

‘We are desperate’

Again in September, the smelter pressed the officials: “Are you able to advise how quickly this can be finalised please?

“We have a backlog of [SCL] material that we are wishing to expedite urgently.”

But the EPA had higher priorities, it replied, to process applications that have a statutory timeframe, which hazardous waste does not.

The emails suggest EPA was feeling the pressure.

In October staff emailed each other: “The applicant has requested urgent processing as they have a backlog of material which they wish to expedite urgently and the application was lodged back in June 2021.”

And a few days later this from the company, by voicemail:

“Can you please let me know urgently where this is at?

“We are desperate to be able to get this under way as this permit forms part of the commitments we have made to [Environment] Minister [David] Parker and others to accelerate our exports of this waste material.”

Minister Parker had said earlier in 2021 he was frustrated to be “flying blind” on contamination at Tiwai, although by then he had received at least 170 pages of reports on it from officials.

In late October 2021, the effort to sign-off the export of just a fraction of the toxic waste at Tiwai Pt still faced a stack of countries it needed approval from.

These were finally secured and sorted by early this year.

In April this year, the company laid out its preliminary closure and clean-up plan.

Surrounding that, it had been providing regular fulsome updates on what was being found in the hundreds of boreholes newly drilled to assess the state of the land and water around the smelter.

It had a sweetheart electricity deal with Meridian, and its fraught talks with the government in which it said a sweet power transmission deal too was a make-or-break for Rio Tinto, have faded into recent history.

This week, the company’s chief executive Chris Blenkiron said the massive jump to almost $700m in provision for clean-up and closure “ensures our community can be confident we are putting the right plans in place”.

“In the meantime,” he said, “work is already under way to remove waste as part of our commitment to continue to improve our environmental performance.”

It has a lot of work to do.